What to Know

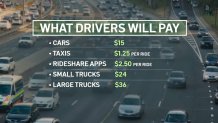

- Cars will be charged an additional $15 to enter Manhattan at 61st Street and below, while trucks could be charged between $24 and $36, depending on size. It could take effect as early as mid-June; only a lawsuit can stop it now, and the MTA says it doesn't expect that to happen

- There are some planned exemptions. Most of those will likely include government vehicles. Yellow school buses with a contract with the DOE are also in the clear, as are city-owned vehicles

- The MTA board overwhelmingly voted to approve congestion pricing in December, saying charging drivers to enter a swath of Manhattan would contribute millions of dollars to the aging transit system

As the clock ticks down to the start of congestion pricing in New York City (slated to start two months from Monday), there's a last-ditch push to repeal the controversial tolling plan.

But will the eleventh-hour legislative maneuver even work, or will it be too little too late?

On Staten Island, New York State Assemblyman Michael Tannousis called on his colleagues in Albany to repeal the congestion pricing toll set to be imposed on drivers.

"I implore you, reach out to senators and sign on to this bill," Tannousis said.

He and other fellow Republicans think opposition is growing.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

"I guarantee you more than half the Democrats are opposed but are afraid to say it publicly," said Rep. Nicole Malliotakis.

News

But the MTA does not seem phased.

"I have a lawn chair in front of my apartment for any congestion denier to see what it’s like in Hell’s Kitchen every day," said NYC Transit President Rich Davey, reminding opponents of the projected $15 billion in revenue that congestion pricing is expected to generate.

That money would pay for construction projects like revamped subway stations — or elevators, which are still needed at hundreds of stations.

On Monday, transit officials showed off new electric vans for disabled riders, who have testified that they're tired of getting stuck in traffic.

"one of the difficulties we have is that our trips are long," said accessibility advocate RueZalia Watkins.

Still, those looking to repeal the plan remain skeptical that tolls will pay for what the MTA promises. But transit officials say future improvements depends on congestion pricing.

"If they have better ideas on how to make investments like these," Davey said. "I'm sure they don't."

In March, a majority of the MTA board voted congestion pricing, greenlighting the controversial plan that will charge cars $15 to enter Manhattan below 61st Street and hit trucks with even higher tolls starting in just a few months.

Only one of the 12 board members opposed the proposal.

That approval, essentially a rubberstamp of "clarifications" like exemptions, given the plan itself was approved last year, means congestion pricing can begin following a 60-day public information campaign and a concurrent 30-day testing period.

All 108 toll readers are already installed and ready to go, positioning the MTA to begin collecting as soon as June 15. Federal judges on either side of the Hudson River could still block the plan, though the MTA expects that not to be the case.

The board overwhelmingly voted in favor of the plan in December, saying charging drivers to enter a swath of Manhattan would contribute millions of dollars to the aging, cash-strapped transit system. The MTA has said the plan will deliver $15 billion that will help pay for new trains and signals, as well as other fixes to modernize the aging system.

Get details on the planned exemption list here — like school buses, commuter buses and essential government vehicles owned by the city.

"We are not talking about commissioners' vehicles, not elected officials' vehicles. They are not exempt," said MTA Deputy Chief of Policy Juliette Michaelson.

Not exempt? New Jersey drivers, though lawsuits could change theoretically change that. But those seem like longshots.

The toll will not be in effect for taxis, but drivers will be charged a $1.25 surcharge per ride. The same policy applies to Uber, Lyft and other rideshare drivers, though their surcharge will be $2.50.

Despite what MTA officials say were overwhelming public comments "in favor" of congestion pricing by a 2-to-1 margin, a number of groups have stood in opposition.

Taxi advocates have blasted the plan, calling it "a reckless proposal that will devastate an entire workforce."

Public hearings earlier in March paved the way for Wednesday's vote. For its part, the MTA has insisted that it is merely implementing a state law aimed at cleaning the air and modernizing mass transit.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy -- who long shared his opposition to the measure given that many of his constituents would be impacted by congestion pricing given that they work in Manhattan -- shared his discontent with the final decision, saying in a statement: "This is far from over and we will continue to fight this blatant cash grab. The MTA’s actions today are further proof that they are determined to violate the law in order to balance their budget on the backs of New Jersey commuters. We will continue to avail ourselves of every option in order to protect residents on this side of the Hudson from an unfair tolling scheme that discriminates against New Jerseyans, especially lower and middle-income drivers."

How does congestion pricing work?

Congestion pricing will impact any driver entering what is being called the Central Business District (CBD), which stretches from 60th Street in Manhattan and below, all the way down to the southern tip of the Financial District. In other words, most drivers entering midtown Manhattan or below will have to pay the toll, according to the board's report.

All drivers of cars, trucks, motorcycles and other vehicles would be charged the toll. Different vehicles will be charged different amounts — here's a breakdown of the prices:

- Passenger vehicles: $15

- Small trucks (like box trucks, moving vans, etc.): $24

- Large trucks: $36

- Motorcycles: $7.50

The $15 toll is about a midway point between previously reported possibilities, which have ranged from $9 to $23.

The full, daytime rates will be in effect from 5 a.m. until 9 p.m. each weekday, and 9 a.m. until 9 p.m. on the weekends. The board called for toll rates in the off-hours (from 9 p.m.-5 a.m. on weekdays, and 9 p.m. until 9 a.m. on weekends) to be about 75% less — about $3.50 instead of $15 for a passenger vehicle.

Drivers will only be charged to enter the zone, not to leave it or stay in it. That means residents who enter the CBD and circle their block to look for parking won't be charged.

Only one toll will be levied per day — so anyone who enters the area, then leaves and returns, will still only be charged the toll once for that day.

The review board said that implementing their congestion pricing plan is expected to reduce the number of vehicles entering the area by 17%. That would equate to 153,000 fewer cars in that large portion of Manhattan. They also predicted that the plan would generate $15 billion, a cash influx that could be used to modernize subways and buses.

Can I get a discount?

Many groups had been hoping to get exemptions, but very few will avoid having to pay the toll entirely. That small group is limited to specialized government vehicles (like snowplows) and emergency vehicles.

Low-income drivers who earn less than $50,000 a year can apply to pay half the price on the daytime toll, but only after the first 10 trips in a month.

While not an exemption, there will also be so-called "crossing credits" for drivers using any of the four tunnels to get into Manhattan. That means those who already pay at the Lincoln or Holland Tunnel, for example, will not pay the full congestion fee. The credit amounts to $5 per ride for passenger vehicles, $2.50 for motorcycles, $12 for small trucks and $20 for large trucks.

Drivers from Long Island and Queens using the Queens-Midtown Tunnel will get the same break, as will those using the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Those who come over the George Washington Bridge and go south of 60th Street would see no such discount, however.

Public-sector employees (teachers, police, firefighters, transit workers, etc.), those who live in the so-called CBD, utility companies, those with medical appointments in the area and those who drive electric vehicles had all been hoping to get be granted an exemption. They didn't get one.

UFT President Michael Mulgrew, one of the lead plaintiffs in a federal lawsuit again congestion pricing, said following the MTA approval that now it's the courts' job to step in.

"Now that the MTA board has voted, it is going to be up to the courts to prevent the huge environmental injustice that threatens families outside the Manhattan congestion zone, including communities that are already suffering some of the worst air pollution and asthma rates in the country," Mulgrew said.