What to Know

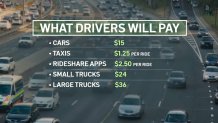

- Cars will be charged an additional $15 to enter Manhattan at 61st Street and below, while trucks could be charged between $24 and $36, depending on size

- There are some planned exemptions. Most of those will likely include government vehicles. Yellow school buses with a contract with the DOE are also in the clear, as are city-owned vehicles

- The MTA board overwhelmingly voted to approve congestion pricing in December, saying charging drivers to enter a swath of Manhattan would contribute millions of dollars to the aging transit system

June 30.

That's when car drivers will be charged an additional $15 to enter Manhattan at 61st Street and below, while trucks could be charged between $24 and $36, depending on size.

The long-awaited congestion pricing model set to make history in the United States will begin in New York City one second after 12 a.m. on the final Sunday in June, MTA officials announced. The date is two weeks later than the transit agency had initially targeted.

“We are finally doing something about it and joining world cities like London and Stockholm that have implemented congestion pricing," MTA Chairman Janno Lieber said.

Most of the cars likely to get full exemptions will be government vehicles. Get details on the planned exemption list here — like school buses, commuter buses and essential government vehicles owned by the city.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

Not exempt? New Jersey drivers, though lawsuits could change theoretically change that. Though the MTA did not seem terribly concerned about that prospect.

News

The toll will not be in effect for taxis, but drivers will be charged a $1.25 surcharge per ride. The same policy applies to Uber, Lyft and other rideshare drivers, though their surcharge will be $2.50.

In late March, all but one MTA board member green-lit a plan that will, in less than two months, start charging cars $15 to enter Manhattan below 61st Street. Trucks will see higher tolls.

All 110 toll readers are installed, positioning the MTA to be ready to collect by June. Federal judges on either side of the river could delay the plans, but the MTA has said it expects those legal challenges to fail.

Congestion pricing itself was approved in December. The MTA board voted overwhelmingly in favor, saying charging drivers to enter a swath of Manhattan would contribute millions of dollars to the aging, cash-strapped transit system. The MTA has said the plan will deliver $15 billion that will help pay for new trains and signals, as well as other fixes.

How does congestion pricing work?

Congestion pricing will impact any driver entering what is being called the Central Business District (CBD), which stretches from 60th Street in Manhattan and below, all the way down to the southern tip of the Financial District. In other words, most drivers entering midtown Manhattan or below will have to pay the toll, according to the board's report.

All drivers of cars, trucks, motorcycles and other vehicles would be charged the toll. Different vehicles will be charged different amounts — here's a breakdown of the prices:

- Passenger vehicles: $15

- Small trucks (like box trucks, moving vans, etc.): $24

- Large trucks: $36

- Motorcycles: $7.50

The $15 toll is about a midway point between previously reported possibilities, which have ranged from $9 to $23.

The full, daytime rates will be in effect from 5 a.m. until 9 p.m. each weekday, and 9 a.m. until 9 p.m. on the weekends. The board called for toll rates in the off-hours (from 9 p.m.-5 a.m. on weekdays, and 9 p.m. until 9 a.m. on weekends) to be about 75% less — about $3.50 instead of $15 for a passenger vehicle.

Drivers will only be charged to enter the zone, not to leave it or stay in it. That means residents who enter the CBD and circle their block to look for parking won't be charged.

Only one toll will be levied per day — so anyone who enters the area, then leaves and returns, will still only be charged the toll once for that day.

The review board said that implementing their congestion pricing plan is expected to reduce the number of vehicles entering the area by 17%. That would equate to 153,000 fewer cars in that large portion of Manhattan. They also predicted that the plan would generate $15 billion, a cash influx that could be used to modernize subways and buses.

Can I get a discount?

Many groups had been hoping to get exemptions, but very few will avoid having to pay the toll entirely. That small group is limited to specialized government vehicles (like snowplows) and emergency vehicles.

Low-income drivers who earn less than $50,000 a year can apply to pay half the price on the daytime toll, but only after the first 10 trips in a month.

While not an exemption, there will also be so-called "crossing credits" for drivers using any of the four tunnels to get into Manhattan. That means those who already pay at the Lincoln or Holland Tunnel, for example, will not pay the full congestion fee. The credit amounts to $5 per ride for passenger vehicles, $2.50 for motorcycles, $12 for small trucks and $20 for large trucks.

Drivers from Long Island and Queens using the Queens-Midtown Tunnel will get the same break, as will those using the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Those who come over the George Washington Bridge and go south of 60th Street would see no such discount, however.

Public-sector employees (teachers, police, firefighters, transit workers, etc.), those who live in the so-called CBD, utility companies, those with medical appointments in the area and those who drive electric vehicles had all been hoping to get be granted an exemption. They didn't get one.

UFT President Michael Mulgrew, one of the lead plaintiffs in a federal lawsuit again congestion pricing, said following the MTA approval that now it's the courts' job to step in.

"Now that the MTA board has voted, it is going to be up to the courts to prevent the huge environmental injustice that threatens families outside the Manhattan congestion zone, including communities that are already suffering some of the worst air pollution and asthma rates in the country," Mulgrew said.