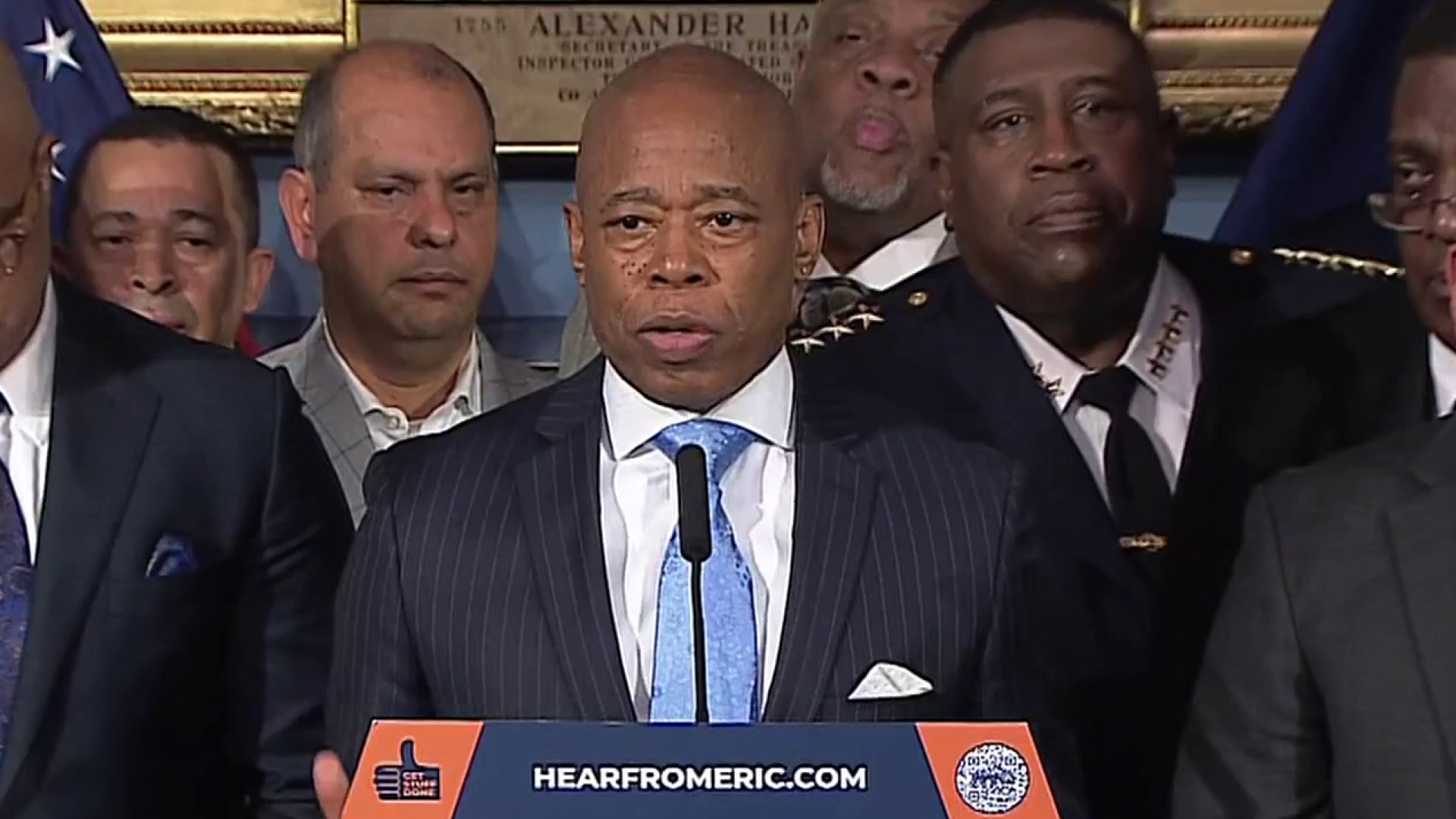

The New York City Council could override a veto from Mayor Eric Adams on what has been called the "How Many Stops" Act — so what does it all mean for police and residents? Here's a breakdown.

The bill, which passed through City Council at the end of 2023 by a 35-9 margin and seven abstentions, was vetoed by Adams earlier in January, setting up a battle with the legislative body.

There are 51 members of City Council, and it will take 34 votes to override the mayor's veto.

The council override vote is set for Tuesday afternoon. City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams said she was "very confident" there were enough votes in favor of the bill to make it veto-proof.

What does the "How Many Stops" Act do, and why is it controversial?

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

The act would require the NYPD to log all public interactions, which advocates have emphasized will support transparency in the department. But critics have said it creates too much paperwork and can slow down police work.

What's actually in the bill? Police officer doing any investigation would need to note:

- Race, ethnicity, gender and age of all people they talk to in connection with the case.

- The "reason for the investigative encounter"

- Whether the individual was stopped "based on observations, response to a dispatch from a police radio, witness or another basis"

- Whether a summons was issued or an arrest made

- Whether there was any use of force

Michael Sisitzky of the NYCLU, which is in support of the bill, said that the bill wouldn't add all that much work than police already do.

"It is the baseline level of transparency to know where stops are happening and basic information — why they’ve been approached by an officer," said Sisitzky. "NYPD officers have department-issued smartphones where they do reports already just by clicking drop-down menus between deployments."

But Mayor Adams has said while he supports the spirit of the bill, he thinks it will hurt public safety. By forcing officers to record every witness in a missing persons case, for example, it could drastically slow them down and slow down the investigation, and delay finding the individual.

"Say you talk to 1,000 people — that’s 3,000 extra minutes. Forty-nine hours. Two full days," the mayor said.

Police are required to document information on major investigation, such as who they talk to and where. But it's not the case for day-to-day routine stops.

Police made a last ditch effort Monday night to convince lawmakers public safety is on the line, arguing it’ll lead to officers spending more time filling out paperwork rather than fighting crime.

"It takes our time away from the street. It affects response time and ultimately it affects the community," said NYPD Chief of Patrol John Chell. "They call it level one stops. It’s an encounter, it’s an inquiry. It has nothing to do with suspicion. It has nothing to do with stopping someone. Stopping someone is implying they’re not free to go. Level one encounter, people are free to go. They don’t have to speak to us. They can keep walking."

NYPD stop of Councilman Yusuf Salaam

Putting heat on the debate regarding the bill was the bodycam video release of Yusuf Salaam being pulled over this past weekend. Salaam, whom many will recall was one of the Exonerated Five, was pulled over Friday night for driving a car with improperly tinted windows.

Salaam was elected to City Council in 2023, representing the 9th District in Harlem.

In a statement, Salaam said "I asked the officer why I was pulled over. Instead of answering my question, the officer stated, 'We’re done here,’ and proceeded to walk away."

The NYPD released video of the stop and documentation — seemingly supporting the viewpoint of the bill's defenders.

"My biggest takeaway from that is the police department can put out video whenever they want to," said NYC Public Advocate Jumaane Williams. "It’s not interrupting police work, it actually is police work.”

In regards to the police stop of Salaam, the mayor praised everyone involved.

"I think we are attempting to find a problem when there is no problem. They did it right," said Adams, questioning if the officer was even able to hear Salaam's questions. "It was on a street, there was noise, I don’t know if the officer even heard him."

Chell supported the officer, saying "Harlem should be so proud to have such a professional officer working in Harlem, protecting the streets and courteous to the community. That’s the kind of cop we need in the city and we’re very proud of how he handled that car stop."

Former NYPD Chief of Department Terence Monahan said that the stop "is not the kind of stop that applies to this bill," and it would be "wrong to make this a news story."

But retired NYPD Lieutenant Edward Raymond was not convinced.

"It’s still profiling. That same model with tints in Bay Ridge or the Upper West Side would not be stopped," said Raymond. "Officers are already asked to characterize their body camera footage — this is just additional data."