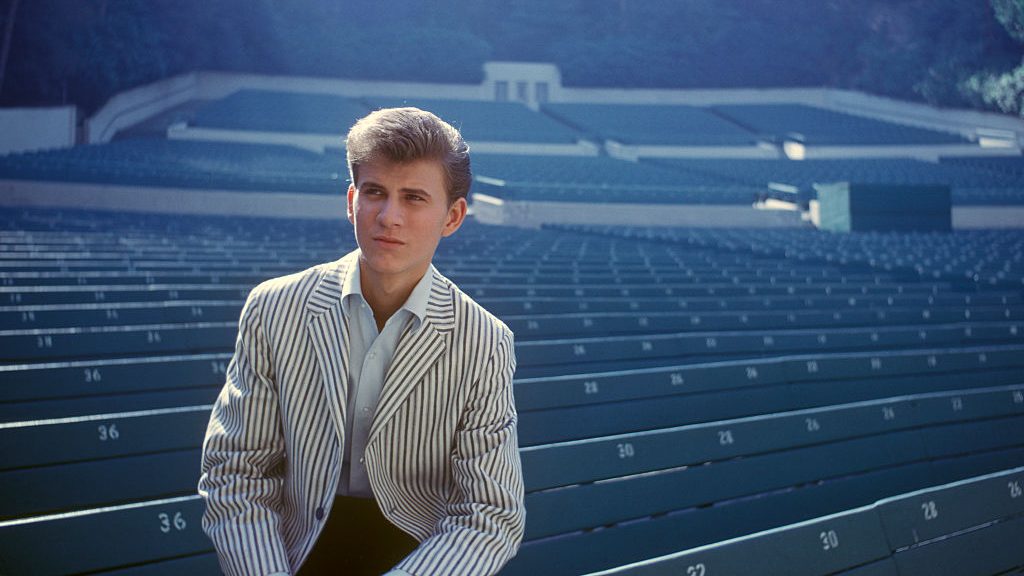

Madeleine Albright fled the Nazis as a child and climbed to the summit of diplomacy and foreign policy in the United States, breaking the glass ceiling as the first female secretary of state and setting the pace for other women to follow.

“She has watched her world fall apart, and ever since, she has dedicated her life to spreading to the rest of the world the freedom and tolerance her family found here in America,” President Bill Clinton said in announcing his historic choice for America's top diplomat in December 1996.

Albright, whose family said she died Wednesday of cancer at age 84, was the daughter of a Czech diplomat, and was born just as Adolf Hitler’s Germany started its move down a path of conquest. The bleak years that followed uprooted Albright’s family and intimidated Europe.

Watch NBC 4 free wherever you are

She grew to be outspoken and advised women years later “to act in a more confident manner” and “to ask questions when they occur and don’t wait to ask.”

“It took me quite a long time to develop a voice, and now that I have it, I am not going to be silent,” Albright told HuffPost Living in 2010.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox with NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

Her determination to use her academic background and her instinct for world affairs, combined with a formidable drive, led to her becoming the first woman to head the State Department. She was not part of the presidential line of succession, however, because of her birth outside the United States.

More Madeleine Albright Coverage

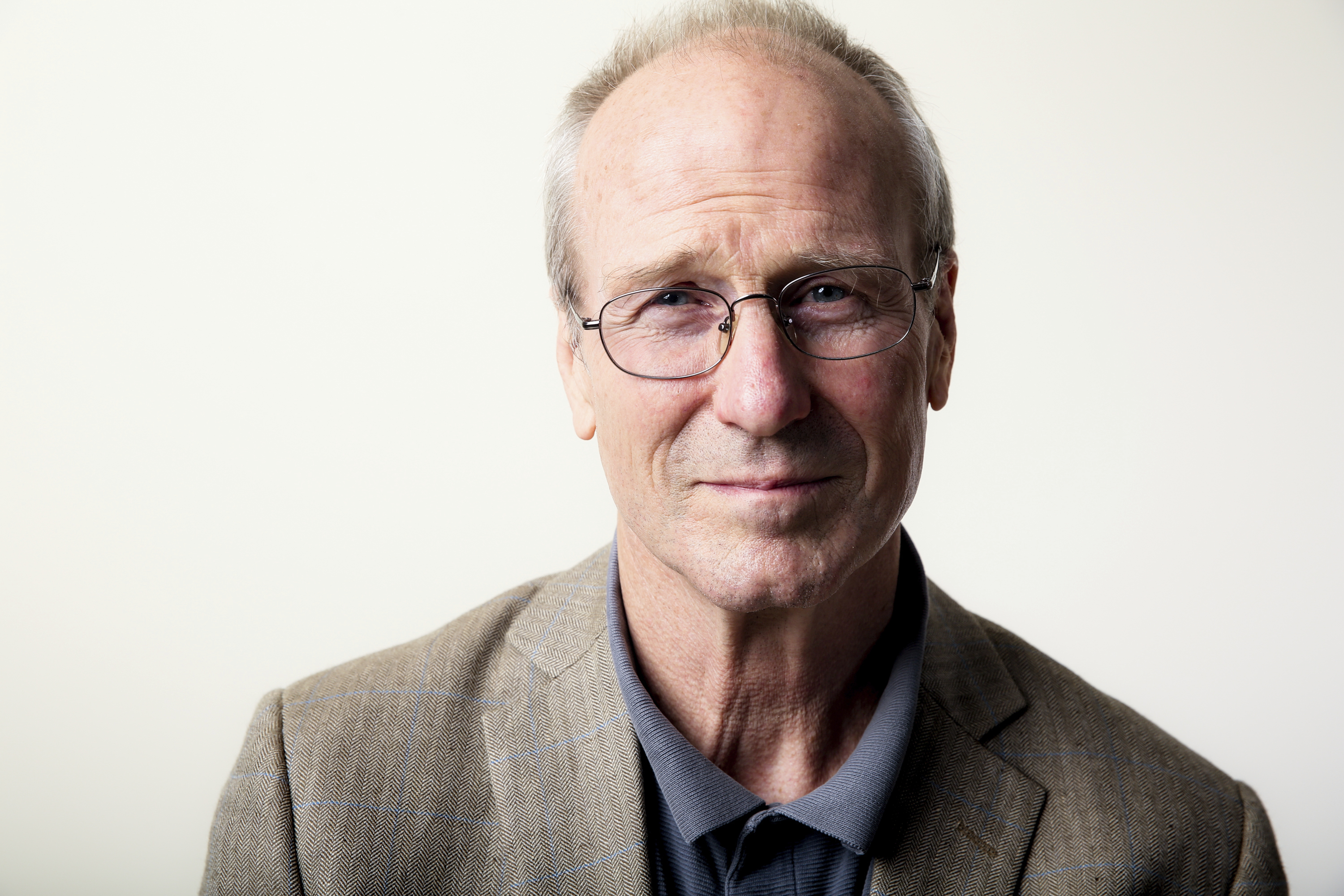

For decades, Albright was a popular professor at Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service, where her “Modern Foreign Governments” was a required course and examined autocracies and the rise and fall of nation states, including in Ethiopia, the Czech Republic and the Soviet Union. A scholar influenced heavily by the Cold War, she also took a profound interest in arms control and was a proponent of combating dictatorships.

Albright remained outspoken after leaving government. She criticized President George W. Bush for using “the shock of force” rather than alliances to foster diplomacy. She said he had driven away moderate Arab leaders and created the potential for a dangerous rift with European allies.

When the Senate Foreign Relations Committee asked her in January 2007 whether she approved of Bush’s proposed “surge” in U.S. troops in bloodied Iraq, she responded: “I think we need a surge in diplomacy. We are viewed in the Middle East as a colonial power and our motives are suspect.”

An internationalist, Albright was shaped in part by her background as a refugee. She played a key role in persuading Clinton to go to war against the Yugoslav leader Slobodan Milosevic over his brutal treatment of Kosovar Albanians in 1999.

“My mindset is Munich,” she said frequently, referring to the German city where the Western allies in 1938 abandoned her homeland to the Nazis.

She helped win Senate ratification of NATO’s expansion and a treaty imposing international restrictions on chemical weapons. She led a successful fight to keep Egyptian diplomat Boutros Boutros-Ghali from a second term as secretary-general of the United Nations; he accused her of deception and posing as a friend.

A Democrat, she was U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in Clinton’s first term, but sought to work with Republicans in Congress on issues ranging from Russia to Cuba. As secretary of state she worked with both political parties to reform the State Department and the U.S. Information Agency, which had run Washington's anti-Soviet messaging since the end of World War II.

Albright advocated a tough U.S. foreign policy, particularly in the case of Milosevic’s treatment of Bosnia. She once exclaimed to Colin Powell, then the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: “What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?”

“Albright has known firsthand what tyranny and totalitarianism can do to ordinary people,” said Michael Zantovsky, a Czech ambassador to Washington. “The lesson of Munich is that you do not appease aggressors, you stick by your friends, and you take a stand for values and principles that you really believe in.”

“I am an eternal optimist,” Albright said in 1998, amid an effort to promote peace in the Middle East. But she said getting Israel to pull back on the West Bank and the Palestinians to rout terrorists posed serious problems.

As secretary of state, she made limited progress at first in trying to expand the 1993 Oslo accords that established the principle of self-rule for the Palestinians on the West Bank and in Gaza.

But in 1998, she played a leading role in formulating the Wye Accords that turned over control of about 40% of the West Bank to the Palestinians. Still, a comprehensive peace in the Middle East between Israel and the Arabs eluded the Clinton administration.

Albright also helped guide U.S. foreign policy during conflicts in the Balkans and the Hutu-Tutsi genocide in Rwanda.

She enjoyed her reputation for plain-speaking. And she turned her love of jewelry into a weapon, telegraphing her messages with the brooch she chose to wear. Called a snake by the Iraqi government under Saddam Hussein, she sported a snake pin during a U.N. debate on Iraq.

“When devious, I wear a spider; when ready to sting, a bee,” she said.

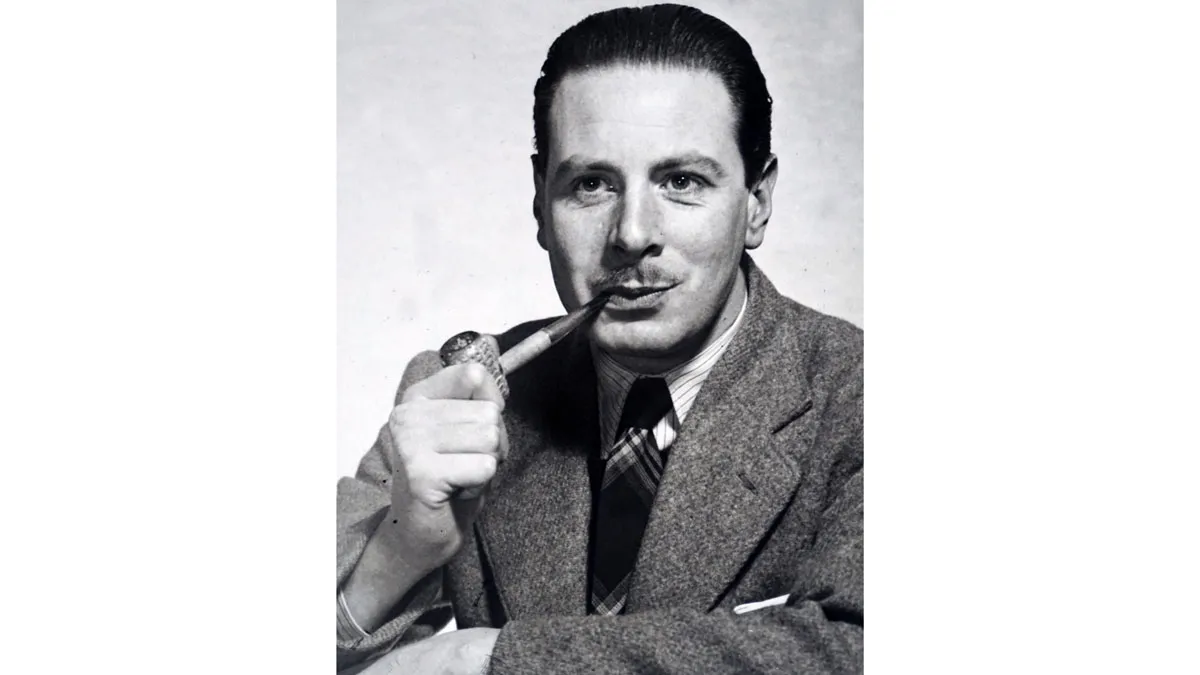

Marie Jana Korbel was born in Prague on May 15, 1937, the daughter of diplomat Joseph Korbel. The family was Jewish and converted to Roman Catholicism when she was 5. Three of her Jewish grandparents died in concentration camps. Albright later said that she only became aware of her Jewish background after she became secretary of state.

The family returned to Czechoslovakia after World War II, before fleeing again, this time to the United States, in 1948, after the communists rose to power. They settled in Denver, where her father obtained a job at the University of Denver.

She married journalist and publishing heir Joseph Albright in 1959, three days after her graduation from Wellesley College. They had three daughters before divorcing in 1983.

Years later, in an interview with biographer Ann Blackman, Albright said: “Do powerful women attract men? My own experience happens to be yes, in a way that was not true before.”

After college she worked as a journalist and later studied international relations at Columbia University, where she earned a master’s degree in 1968 and a doctoral degree in 1976.

Democratic Sen. Edmund S. Muskie launched her career in politics and diplomacy as a legislative assistant in 1976. She later worked for the National Security Council during the Carter administration and advised Democrats on foreign policy before Clinton’s election. He nominated her as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in 1993.

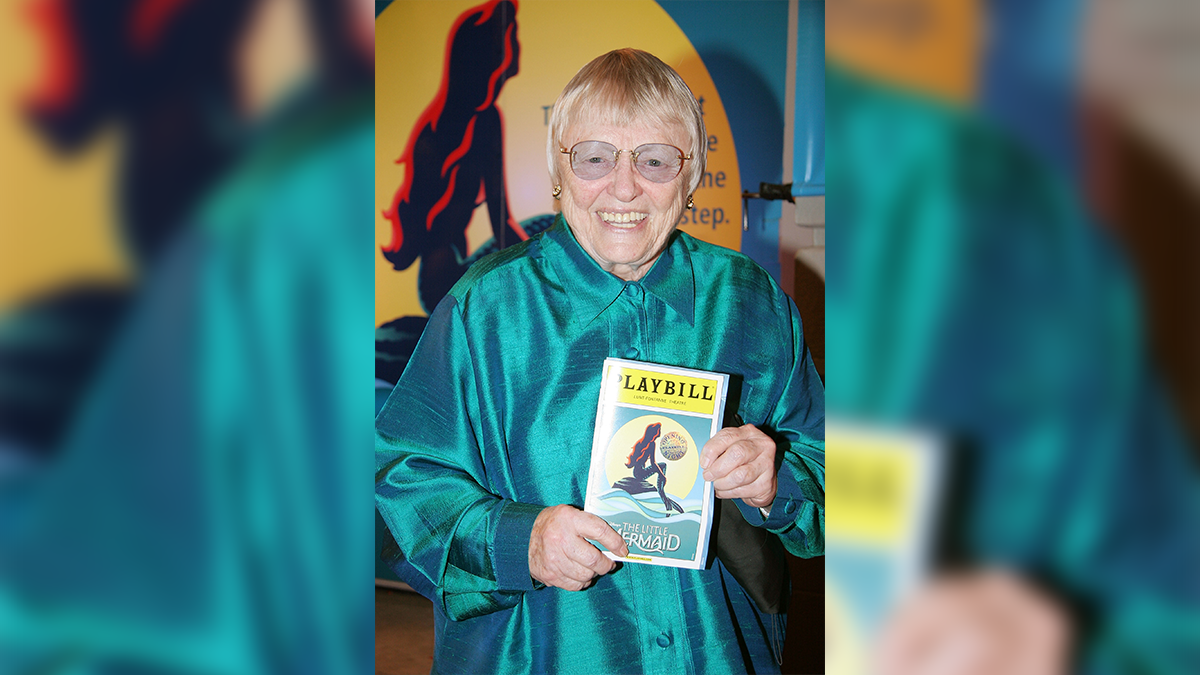

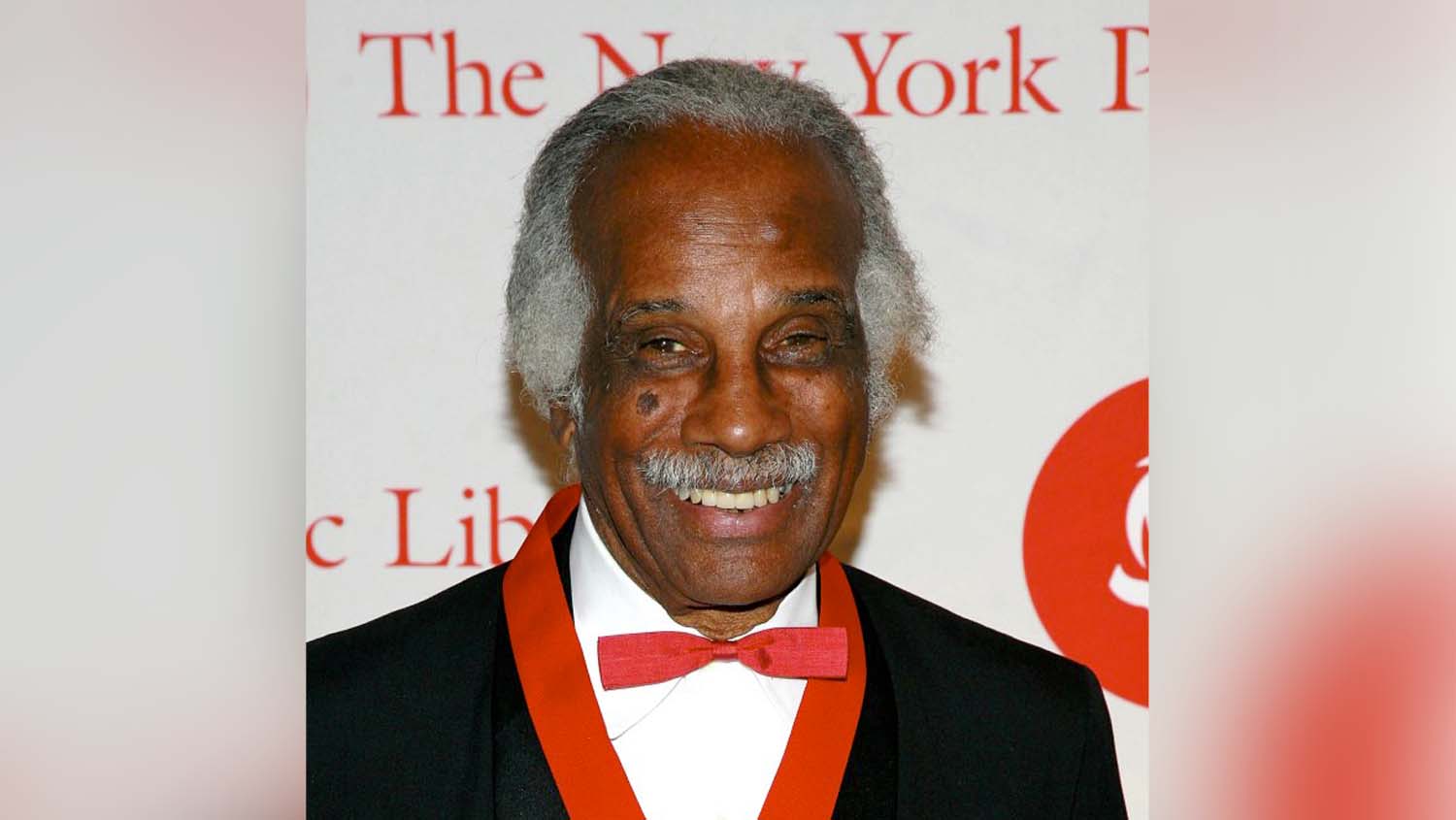

In Memoriam: People We've Lost in 2022

She was fluent in Russian, French and Czech, and knew some Polish, Serbian and German. When meeting in Moscow in 1997 with Russian President Boris Yeltsin, her grasp of Russian was so secure that Yeltsin waved away the interpreter as not necessary.

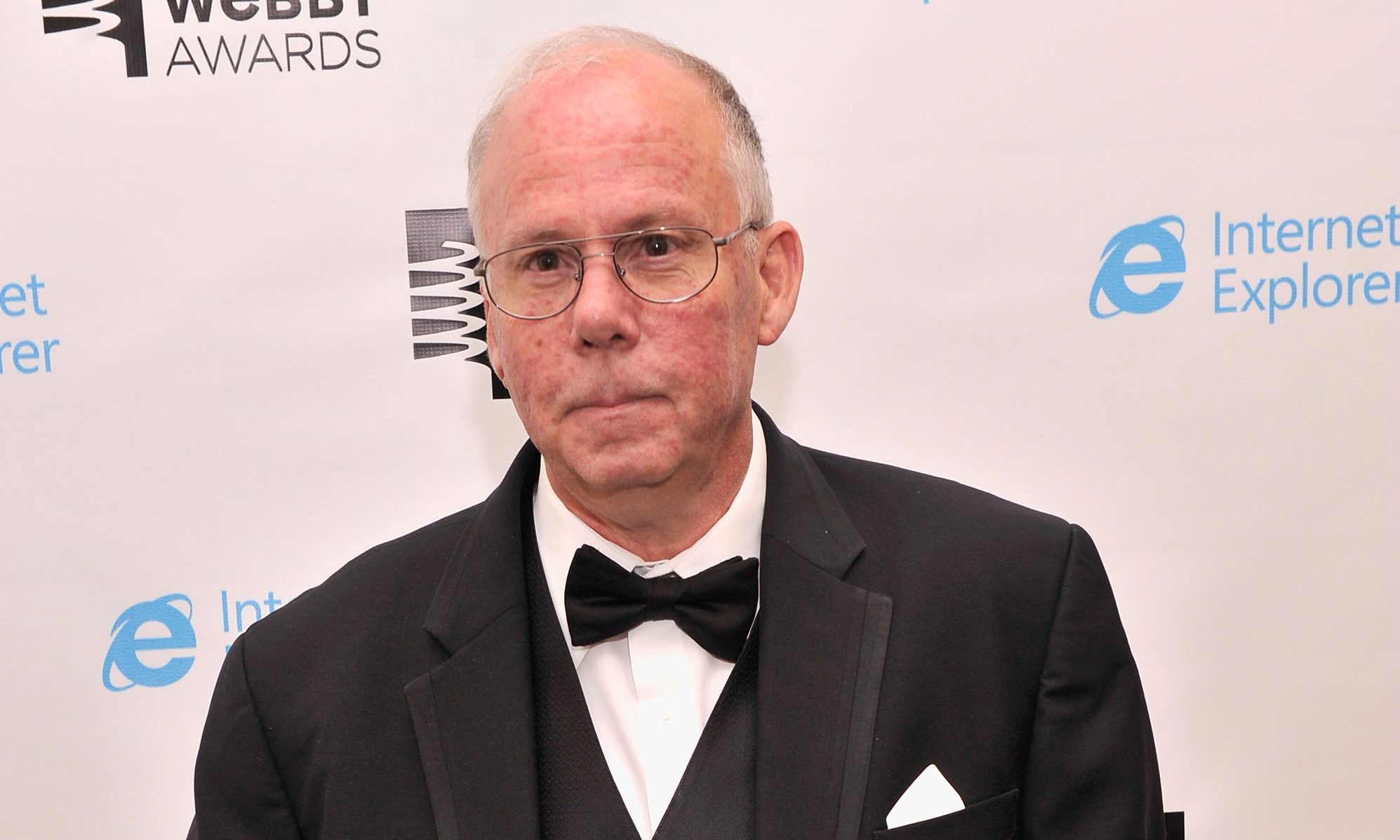

Following her service in the Clinton administration, she headed a global strategy firm, Albright Stonebridge, and was chair of an investment advisory company that focused on emerging markets. She also wrote several books.

She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, by President Barack Obama in 2012.

The late AP Diplomatic Correspondent Barry Schweid contributed to this report.