Follow along with NBC News’ Election Day live updates

Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear won reelection to a second term Tuesday, notching another significant statewide victory in an increasingly red state that could serve as a model for other Democrats on how to thrive politically heading into next year’s defining presidential election.

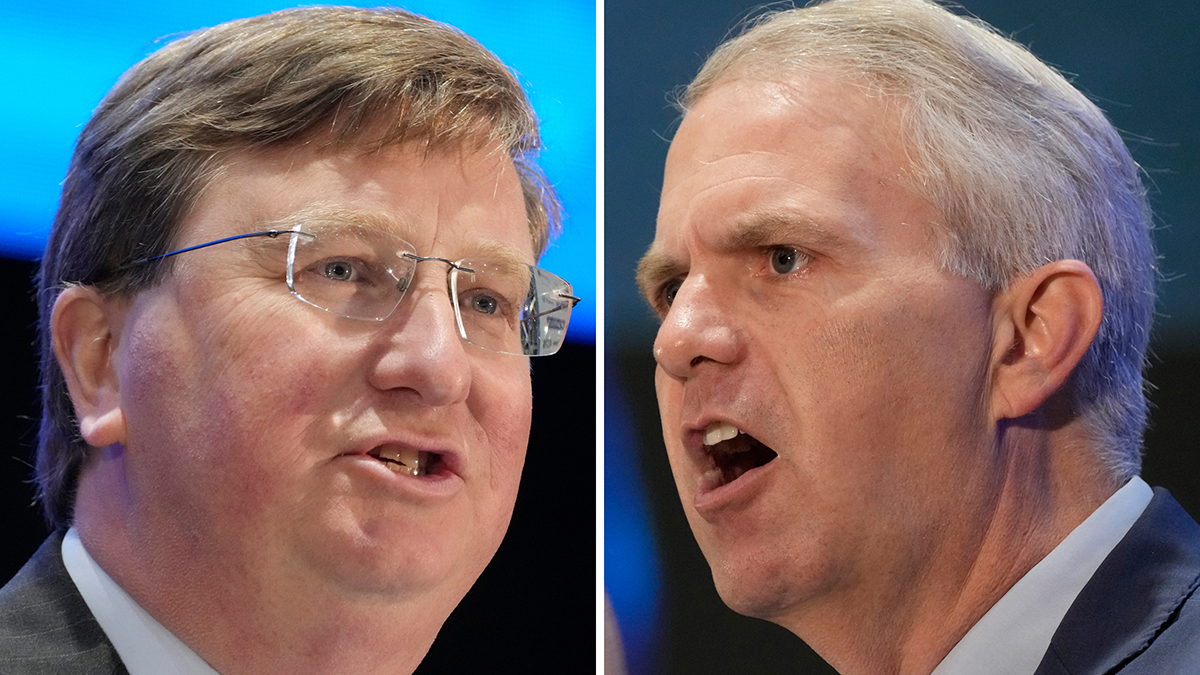

Beshear, 45, rode his stewardship over record economic growth and his handling of multiple disasters, from tornadoes and floods to the COVID-19 pandemic, to victory over Republican Attorney General Daniel Cameron, a protege of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. In what could be a preview of how Democrats campaign in 2024, Beshear hammered Cameron throughout the campaign for his support of the state’s sweeping abortion ban, which makes no exceptions for victims of rape or incest.

The outcome gives divided government another stamp of voter approval in Kentucky, as Republicans hold supermajorities in both chambers of the legislature and continue to dominate the state’s congressional delegation, including both U.S. Senate seats.

Beshear’s victory sustains a family dynasty that has repeatedly defied the Bluegrass State’s tilt toward the GOP. His father, Steve Beshear, is a popular former two-term governor. By the end of Andy Beshear’s second four-year term, a Beshear will have presided in the Kentucky governor’s office for 16 of the last 20 years.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox.> Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

The win, which took place in increasingly difficult political terrain, could position the younger Beshear to join a growing list of Democratic governors flagged as potential contenders for higher office nationally.

The contest with Cameron was a matchup of former law firm colleagues, both of whom have been pegged as rising stars. Cameron made political history in 2019 as Kentucky’s first Black attorney general but was unable to clear the last hurdle to become the state’s first Black governor.

More: Elections

Cameron tried nationalizing the campaign by linking Beshear to Democratic President Joe Biden in a state where Republican ex-President Donald Trump remains popular. Beshear followed his successful campaign formula from 2019, when he narrowly defeated GOP Gov. Matt Bevin, by sidestepping discussion of Biden or Trump, focusing instead on state issues and emphasizing his leadership during a tumultuous first term.

In the end, Cameron was unable to overcome the personal popularity of Beshear, who became a living room fixture across Kentucky with his press conferences during the height of the pandemic. From those briefings, Beshear became known to many Kentuckians as much by his first name as his last. His updates were part reassuring pep talk and part sermon on how to contain the virus.

Throughout the campaign, Beshear offered an upbeat assessment of the state, while Cameron pounded away at the governor’s record and consistently linked it to Biden. Beshear touted the state’s record-high economic development growth and record-low unemployment rates during his term, and said he has Kentucky poised to keep thriving.

Beshear was thrust into crisis management during the pandemic and when deadly tornadoes tore through parts of western Kentucky — including his father’s hometown — in late 2021, followed by devastating flooding the next summer in sections of the state’s Appalachian region in the east. The governor oversaw recovery efforts that are ongoing, offering frequent updates and traveling to stricken areas repeatedly.

Meanwhile, Cameron said Beshear took credit for accomplishments stemming from Republican legislative policies. He blasted the governor’s restrictions during the pandemic, saying the shutdowns crippled businesses and caused learning loss among students. Beshear said his actions saved lives, mirrored those in other states and reflected guidance from the Trump administration.

Hot-button transgender and abortion issues dominated much of the campaign.

Cameron and his GOP allies tried to capitalize on Beshear’s veto of a measure banning gender-affirming care for children, portraying the governor as an advocate of gender reassignment surgery for minors.

Beshear hit back, claiming his foes misrepresented his position while pointing to his faith and support for parental rights to explain his veto. He said the bill “rips away” parental freedom to make medical decisions for their children. Beshear, a church deacon, said he believes “all children are children of God.”

Democrats put Cameron on the defensive on the abortion issue.

They played up Cameron’s support for the state’s existing near-total abortion ban, which offers no exceptions for pregnancies caused by rape or incest. Beshear denounced it as extremist, and his campaign ran a viral TV ad featuring a young woman, now in her early 20s, who revealed she was raped by her stepfather when she was 12 years old. She became pregnant as a seventh grader but eventually miscarried. She took aim at Cameron in the ad, saying: “Anyone who believes there should be no exceptions for rape and incest could never understand what it’s like to stand in my shoes.”

Cameron signaled that he would sign legislation adding the rape and incest exceptions, but days later he resumed a more hardline stance, indicating during a campaign stop that he would support such exceptions “if the courts made us change that law.” It highlighted the complexities of abortion-related politics for Republicans since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade.