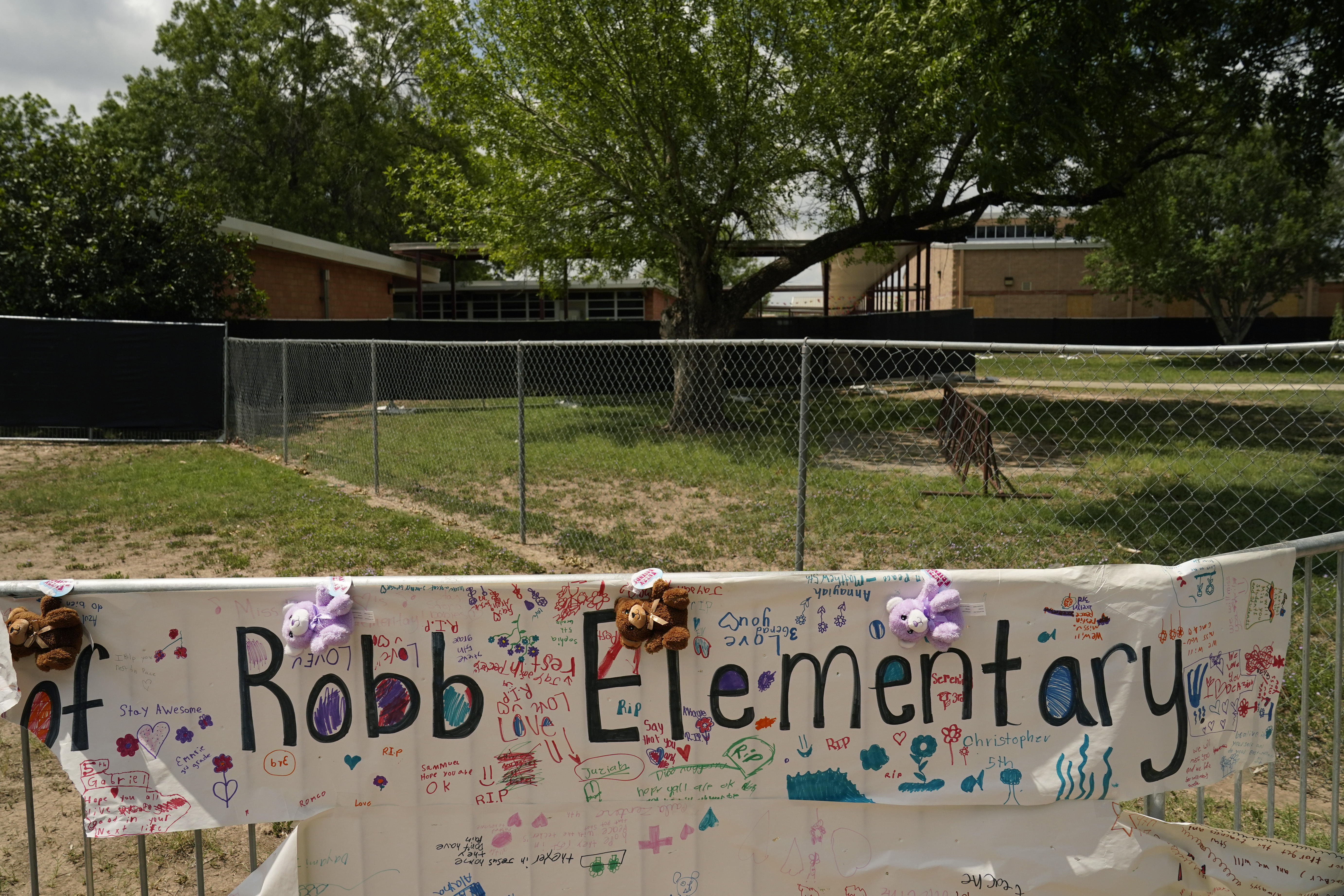

The Uvalde school district’s police chief has stepped down from his position in the City Council just weeks after being sworn in following allegations that he erred in his response to the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School that left 19 students and two teachers dead.

Chief Pete Arredondo said in a letter dated Friday that he has decided to step down for the good of the city and “to minimize further distractions.” He was elected to the council on May 7 and was sworn in on May 31, just a week after the massacre, in a closed-door ceremony.

More Uvalde Shooting Coverage

“The mayor, the city council, and the city staff must continue to move forward to unite our community once again,” Arredondo said in his resignation, first reported by the Uvalde Leader-News.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox.> Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

Arredondo, who has been on administrative leave from the school district since June 22, has declined repeated requests for comment from The Associated Press. NBC News has reached out to Arredondo’s attorney. His attorney, George Hyde, did not immediately respond to emailed requests for comment Saturday.

Texas State Senator Roland Gutierrez told NBC News Saturday that Arredondo has not officially communicated his resignation plans to city leadership.

In a statement Saturday, Uvalde city leadership said they first learned about Arredondo's resignation plans from the Uvalde Leader-News.

Col. Steven McCraw, director of the Texas Department of Public Safety, told a state Senate hearing last month that Arredondo made “terrible decisions” as the massacre unfolded on May 24 , and that the police response was an “abject failure.”

State authorities have described Arredondo as the incident commander during the school carnage. Arredondo has said he did not consider himself to be the officer in charge.

Three minutes after 18-year-old Salvador Ramos entered the school, sufficient armed law enforcement were on scene to stop the gunman, McCraw testified. Yet police officers armed with rifles stood and waited in a school hallway for more than an hour while the gunman carried out the massacre. The classroom door could not be locked from the inside, but there is no indication officers tried to open the door while the gunman was inside, McCraw said.

McCraw has said parents begged police outside the school to move in and students inside the classroom repeatedly pleaded with 911 operators for help while more than a dozen officers waited in a hallway. Officers from other agencies urged Arredondo to let them move in because children were in danger.

“The only thing stopping a hallway of dedicated officers from entering room 111 and 112 was the on-scene commander who decided to place the lives of officers before the lives of children,” McCraw said.

Arredondo has tried to defend his actions, telling the Texas Tribune that he assumed someone else had taken control of the law enforcement response. He said he didn’t have his police and campus radios but that he used his cellphone to call for tactical gear, a sniper and the classroom keys.

It’s still not clear why it took so long for police to enter the classroom, how they communicated with each other during the attack, and what their body cameras show.

Officials have declined to release more details, citing the investigation.

Arredondo, 50, grew up in Uvalde and spent much of his nearly 30-year career in law enforcement in the city.