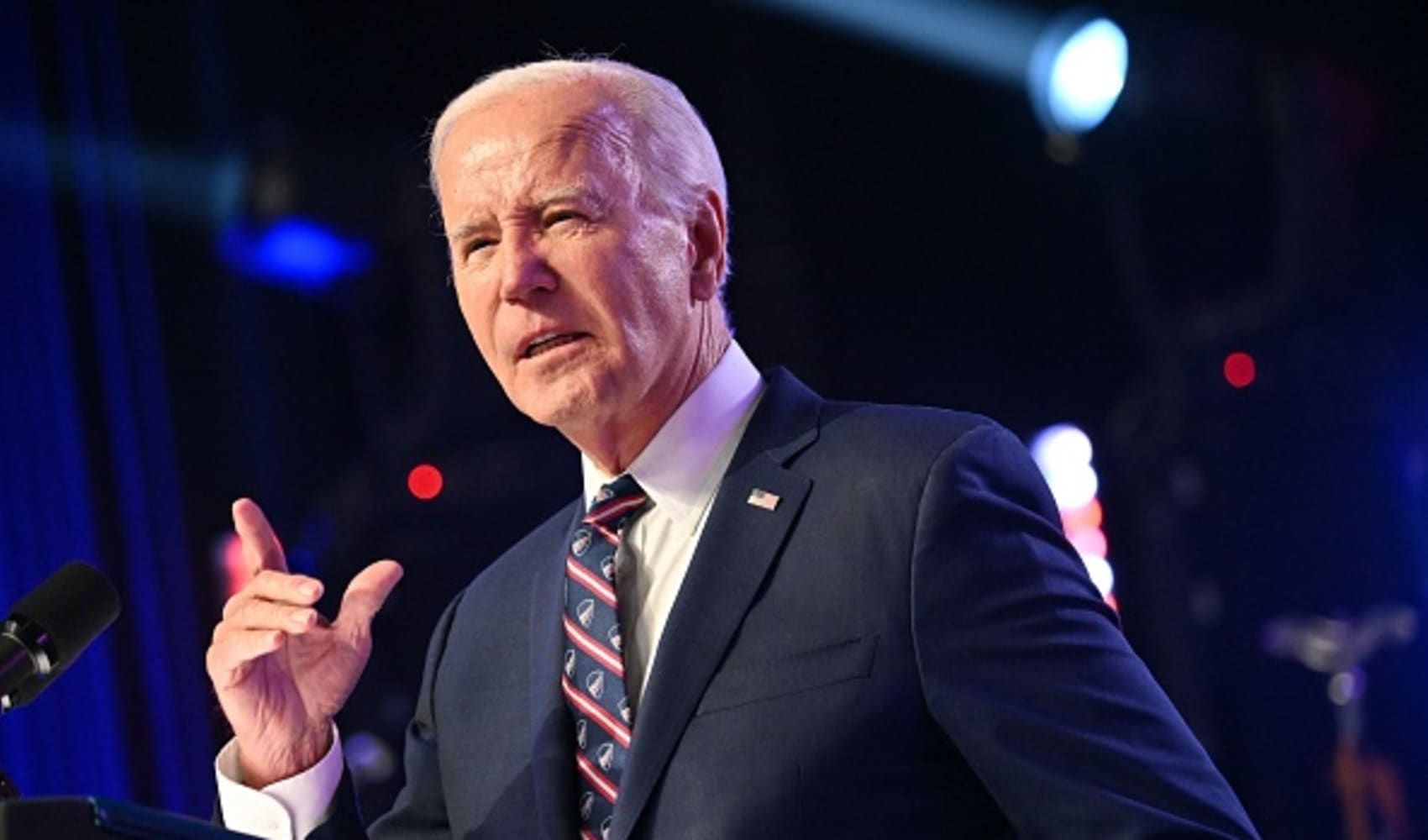

President Joe Biden spoke Thursday to celebrate the easing inflation rates after the Consumer Price Index showed a dip to 6.5%.

President Joe Biden can make an increasingly strong case that he's helped fix inflation — if only he can get voters to believe him.

Figures issued this past week reflected a historic level of progress on battling high prices, hinting that inflation could be near the Federal Reserve's 2% target around the time of November's election. The consumer price index posted an an annual increase of 3.4%, but the prices charged by the producers of goods and services rose a meager 1% over the past year.

Current and former aides say Biden is eager to do more to bring down inflation, after a price surge in 2021 and 2022 crushed his public approval ratings in a way that is dragging down his reelection efforts. They see reasons for optimism with improving consumer sentiment.

“It’s an ongoing effort,” said White House chief of staff Jeff Zients. “Under his leadership, we’ve attacked inflation from every angle.”

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

The question is whether voters are feeling the improvement and will reward Biden. Or will they penalize him because inflation became a problem on his watch as the U.S. emerged from pandemic shutdowns? The answer could hinge on how people feel about the costs of necessities such as gasoline and eggs.

Biden can accurately say his policies helped reduce the average price of a dozen eggs to $2.51, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That is down from a peak last year of $4.82. But Republicans can counter that a dozen eggs cost $1.47 before Biden became president.

Leading GOP lawmakers such as Rep. Jason Smith of Missouri, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, greeted the latest inflation numbers as evidence that voters are still suffering from high prices: “President Biden’s inflation crisis continues to rob the wallets of working families,” he said.

Former President Donald Trump has told supporters that the inflation under Biden is how “countries die” and that Trump's return to the White House would mean lower energy costs.

“Drill, baby, drill,” Trump said in a video posted on social media. “We're going to bring your electric prices way down. We're going to bring your energy prices way down. Gasoline will be back to $2, and maybe even less than that.”

Federal data show that average gas prices did fall below $2 a gallon during Trump's presidency. But that was in early 2020, during the coronavirus pandemic, when schools and businesses were shuttered, sending the U.S. economy into shock as millions lost their jobs. A historic wave of federal government borrowing steadied the U.S. economy during the deadly pandemic.

In 2021, Biden inherited an economy trapped by uncertainty about the pandemic's path. He signed a $1.9 trillion aid package, a sum that Republicans and some economists say triggered the upward scramble of inflation, with the consumer price index registering a four-decade high of 9.1% in June 2022.

Past and current Biden administration officials say the decline in inflation since then was a result of a set of choices. Biden gave the Federal Reserve the political space to increase interest rates. He buttressed supply chains and helped stabilize gas prices. At the same time, the historic burst of job growth under Biden has continued. Outside economists said that would be impossible if inflation were to fall.

Starting with Biden himself, the White House rejected the conventional wisdom that millions of workers might need to lose their jobs to cool demand and ease inflation.

“The president was really focused on using every tool that we had to bring prices down without taking a hatchet to the labor market,” said Bharat Ramamurti, a former deputy director of the White House National Economic Council.

Some aides said job growth helped to fill shortages in an economy recovering from shutdowns tied to the coronavirus. The unemployment rate is a healthy 3.7% and the economy has added about 5 million more jobs so far under Biden’s watch than what the Congressional Budget Office estimated it would before his policies went into effect. Those policies include the bipartisan infrastructure law and spending to increase computer chip production and move the economy away from fossil fuels, as well as reduced insulin prices for people on Medicare.

Biden and many of his aides initially viewed inflation as a result of a squeeze on global supply chains. Factories around the world were still struggling to fully reopen. Shipping container costs jumped tenfold. There were long delays to dock at major U.S. ports. Much of the public saw inflation through the lens of their grocery stores, strip malls and gas stations, but the White House considered it a worldwide issue.

“We showed him international charts that this was happening globally and countries with very different fiscal policies were experiencing different elevations in inflation,” said Jared Bernstein, an aide who is now chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers.

Biden embraced a strategy of improving supply chains by working with the private sector. The ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, California, began to operate nonstop to clear the backlog of ships. The administration helped states reduce the barriers for people trying to get commercial driver's licenses and become truckers.

But the president missed the mark in arguing in July 2021 that the inflation would be “temporary.” Inflation felt far more lasting as it accelerated for nearly a year after Biden's statement.

In a November analysis by the White House, 80% of the decline in the inflation rate since 2022 was due in some form to improved supply chains. Inflation also slowed as the pace of hiring eased with the recovery’s maturing. The major driver of inflation in Thursday’s consumer price index was housing costs, a figure that experts say should decline over the coming months and further reduce the rate of inflation.

Still, the supply chain was not the entire problem for Biden. After Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, food and energy prices jumped as the market saw the risks of shortages caused by the war.

Biden responded in part by releasing a historic 180 million barrels of oil from the U.S. strategic reserves.

Some analysts and Republicans played down the release as a Band-Aid to a larger problem, but the White House argued that the daily release of 1 million barrels over the next six months would provide a bridge until U.S. oil production could increase.

Since the release was announced in March 2022, average daily U.S. oil production has risen by 1.44 million barrels. The country pumped out a record average of 13.25 million barrels a day in October.

Republican lawmakers often criticize Biden for not being friendlier to oil drilling. But the data suggest that the U.S. market responded to the initial lure of high prices by increasing production and thus limiting the risk of inflation going forward, despite the turmoil with the Israel-Hamas war and recent Houthi attacks of ships in the Red Sea.

Still, the Biden administration has made support for renewable energy one of its priorities to address climate change. As a result, officials don't talk much about the record domestic oil production.

Ben Harris, a former assistant secretary at the Treasury Department, said the release and a price cap on Russian oil ensured “there was not a 1970s style oil shock.”

But voters are far from reassured.

Fully 65% of U.S. adults at the end of last year disapproved of how Biden has handled the economy, according to a survey by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs.

By contrast, in March 2021 when the pandemic aid became law and inflation was just 2.6%, 60% of adults said they approved of Biden's economic leadership.