In-vitro fertilization is one of the most common infertility treatments, but less than 50 years ago, researchers and the women among them were still working to create and develop the procedure that now accounts for thousands of births in the U.S. each year.

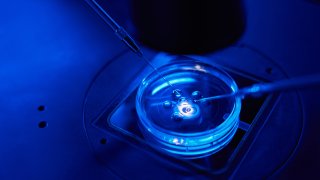

IVF is a medical procedure in which an egg is fertilized by sperm in a lab or elsewhere outside of the body, and the fertilized eggs, or embryos, are then placed into the body, according to the Mayo Clinic.

In February 2024, IVF was at the center of much discussion when the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos created through IVF were considered children under state law. This halted IVF procedures around the state until a law was passed to protect IVF providers in March. It shined a light on the legacy of this procedure and the women involved in its creation who have given families a pathway to having children when there was none.

Watch NBC 4 free wherever you are

Many women scientists played a role in the development of IVF, from Miriam Menkin in the 30s to Georgeanna Seegar Jones in the late 70s and 80s, Margaret Marsh, a historian of reproductive medicine and reproductive sexuality at Rutgers University, and Dr. Wanda Ronner, a professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Pennsylvania, tell TODAY.com.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox with NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

"They were all pioneers in in this area, along with the people they worked with," Marsh says. As research partners to the men developing IVF at the time, the women involved in the formation of IVF were instrumental to the treatment so many people rely on today. "These men could not have been successful without these women," Ronner notes.

Jones' work, for example, led to the birth of the first baby born in the U.S. from IVF, Elizabeth Carr. Carr tells TODAY.com she considers Jones to be "the brains" behind the Jones Institute, the IVF clinic in Norfolk, Virginia, where she was born.

U.S. & World

"She's really the one (who) figured out all the hormone protocols that we all know so well now that are involved in IVF," Carr says. "Throughout her career, she never gave up on this idea of trying to solve this problem of infertility. So, I'm forever eternally grateful to her for that."

In honor of Women's History Month, read on to learn about some of the women who helped make IVF possible.

Miriam Menkin

Menkin started working with Harvard gynecologist Dr. John Rock from the late 1930s to 1950s. Together they determined exactly how fertilization occurs in women — something unknown at the time, Marsh and Ronner, who have co-authored several books about the history of reproductive health, said.

Rock, along with embryologist Arthur Hertig, conducted two pioneering studies focused on IVF, Marsh said, the first of which determined exactly when the human embryo forms during conception. (Rock also played a major role in the development of the birth control pill.)

The second part of Rock's research agenda "could not have been done without the assistance of Miriam Menkin, who was his lab tech," Marsh said. Menkin's role in the experiment was to retrieve eggs from women who were undergoing surgical procedures, Marsh said.

"She would be the one standing outside of the operating room, waiting to receive this egg," Marsh said. Then, using sperm donated from fellows or medical students, Menkin would go to a nearby lab and try to fertilize the egg — "an egg you can't even see," Marsh points out.

Menkin began her attempts to fertilize an egg in 1938, using 138 eggs that resulted in 47 inseminations over the course of six years, Marsh said. Menkin and Rock eventually became the first people to fertilize an egg in vitro, or outside of the body, in 1944.

"Menkin was absolutely imperative to Rock's success. Without her, Rock would not have been able to achieve this. He was the surgeon, he was taking out the tissue, but she was the person in the lab, trying to get these eggs fertilized," Marsh said.

"Menkin was one of probably hundreds of unsung women scientists," Marsh points out. Some had doctorate degrees and others, like Menkin, didn't. But, she stands out in history because she was recognized early-on. Rock made it a point to recognize her work, something which wasn't common at the time.

Because of her ground-breaking work, Menkin was listed as first author on their research article.

Jean Purdy

After Rock and Menkin's article was published in Science, a medical journal, in 1944, showcasing the results of their IVF experiment, British researchers Robert Edwards, a biologist, and Patrick Steptoe, a gynecologist, began working on using IVF to conceive a baby.

Edwards' research assistant and technician, Jean Purdy, would go on to play a vital role in this work in 1968. Purdy, who was trained as a nurse, began teaching herself embryology as she worked with the pair, Marsh says, and the three combined their research in 1973.

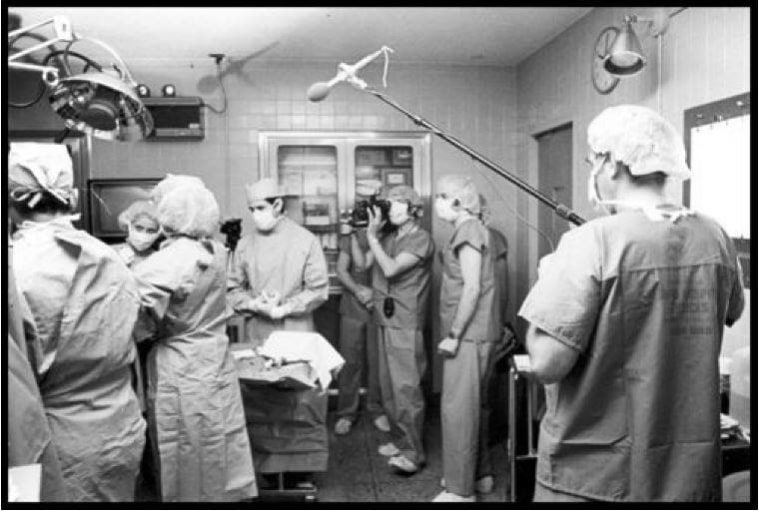

Purdy was responsible for combining the egg with the sperm and fertilizing the embryo, which was a tough task. "(Purdy and the team) tried many different mechanisms to get a pregnancy through IVF, but they were not succeeding," Marsh said.

But, by 1978, Louise Brown became the first baby in the world who was born through IVF on July 25, thanks to Edwards, Steptoe and Purdy's work.

"In England, there was a lot of skepticism about (IVF). They said they weren't sure that it could be done," Marsh explained. The public feared those born via IVF would somehow be different than those who weren't.

Steptoe, Edwards and Purdy went on to found an IVF clinic in 1980, when Purdy was about 35 years old. But she died shortly thereafter from melanoma, just before she turned 40.

"She was very young and extremely talented," Marsh notes.

Edwards, one of Purdy's two research partners, was later awarded the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine for his work developing IVF in 2010, by then both Purdy and Steptoe had died.

"I think that the situation is that today there’s a lot of behind-the-scenes folks in medicine and science that really don’t get recognition at all," Marsh said. "I think that was the case then, and that was the case now."

"She made an incredibly important contribution," Marsh said of Purdy. "Edwards and Steptoe always told everybody that she was an equal partner."

Georgeanna Jones

Georgeanna Jones had her first major discovery in medical school and became a distinguished reproductive endocrinologist who would play a vital role in the development of IVF in the U.S., Marsh said.

Jones worked alongside her husband Howard Jones at Johns Hopkins University, where they shared an office and even a desk at times, until they were forced into mandatory retirement by the university when they turned 65.

According to Marsh's research, the pair were not ready to retire and were offered positions at a brand new medical school, Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia. The day the couple drove down to Virginia for their new jobs was the same day the first IVF baby, Louise Brown, was born.

Coincidentally, Marsh said, the couple had mentored Robert Edwards, the British biologist who worked with Purdy and Steptoe in the U.K., when he was trying to learn how to fertilize eggs.

When a reporter asked Howard Jones if a baby could be born from IVF in the U.S., he and his wife began working on accomplishing an IVF birth in 1978, though they did have opposition from the anti-abortion movement concerned with the morality of IVF.

The pair had the backing from their medical school and opened an IVF clinic, which resulted in the first baby born in the U.S. from IVF on Dec. 28, 1981 — Elizabeth Carr.

"There were very few women in reproductive endocrinology in this time — very few women who were IVF pioneers — and she was one," Marsh said of Georgeanna Jones.

During this time was a number of other women IVF pioneers working throughout the 1980s like Jones, Marsh says. There was Anne Colston Wentz, whose team at Vanderbilt University was the fourth program in the U.S. that had a successful IVF birth in 1983.

PonJola Coney was a fellow at Pennsylvania Hospital, which had its first IVF birth in 1984. Coney was one of the only Black American IVF pioneers at the time, according to Marsh's research, and she went on to direct the first IVF program in Oklahoma at the University of Oklahoma.

Elizabeth Carr

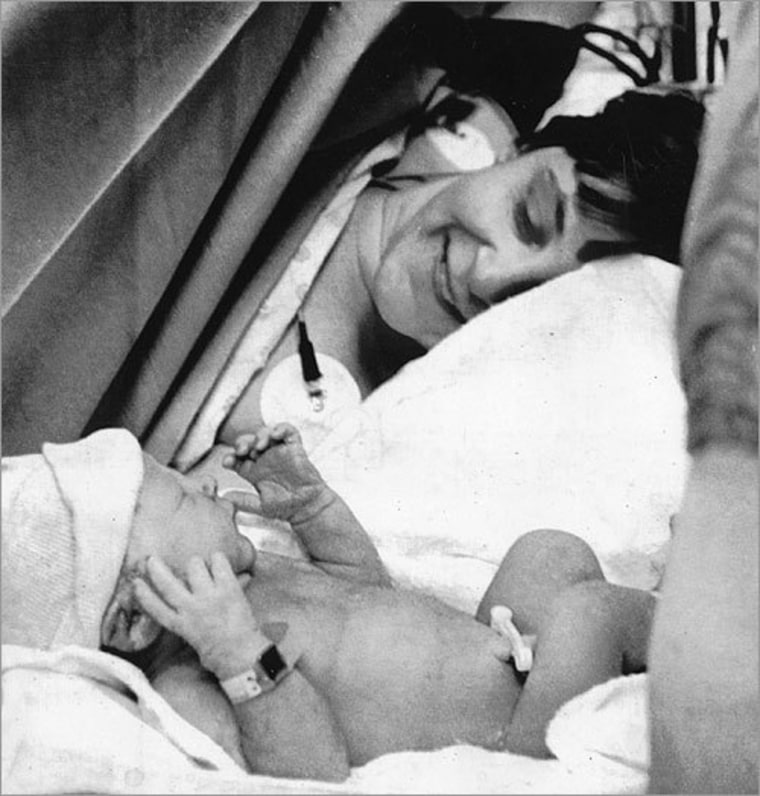

Carr was the first baby born via IVF in the U.S.

Now, 42-year-old patient advocate living in Massachusetts, she tells TODAY.com that she's known about IVF for as long as she can remember — and even before then, as she notes she attended her first press conference when she was just three days old.

Carr's mother experienced three ectopic pregnancies while trying to have children, and after going to a check up, her OBGYN slipped her a copy of a paper talking about IVF and said, while it had only been done in England, it could be something for her to consider, Carr says.

"Both of my parents figured, what did they have to lose? They didn't have a child as it was, so they figured this could be another shot," Carr says. "So they figured it was worth taking a step."

Carr was born in December 1981 with armed guards outside of her hospital room and nursery due to the controversy of her birth, according to the Wall Street Journal.

"I truly don't remember when I first heard somebody speak out against IVF. Obviously, I feel like that's always been there as well, and my parents had me under pretty tight security because of the controversy back then," Carr says. "I guess there's always been the naysayers, but I just don't put too much stock into their argument because I think there's probably nothing more natural than people wanting to build the family of their dreams."

For the first few years of Carr's life, she says she attended IVF baby reunions in Norfolk, Virginia, at the clinic where she was born.

"For a while it was just the first, you know, handful of IVF babies," she says. "I think the last one we had was when I was maybe 10 or 11. And I just remember holding babies 1000 and 1001 that were twins from our specific clinic. And at that point, the reunions had to stop because there was too many of us."

And by 2021, 86, 146 infants born, or 2.3% of all infants born in the U.S., were conceived through the use of assisted reproductive technology, which includes procedures like IVF, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Carr attended President Joe Biden's state of the union address in March 2024 following the Alabama Supreme Court ruling, which she says was "really, really tough."

"I read the ruling and immediately was just devastated and heartbroken, not just for how it made me feel personally, which was kind of like a personal attack, but also for all of those people who wanted to be able to access this treatment," she says.

"IVF is currently the single most effective treatment for infertility, and it has a lot of implications outside of infertility," she continues. "If you're a same sex couple looking to build a family, or you're going through cancer treatments and you want to preserve your fertility, or if you want to have genetic testing to screen out for really terrible diseases in your family history. Things like that."

Carr, a mother of a 13-year-old son, says she would love to see IVF protected nationally, greater insurance coverage and greater care coverage and access in the U.S. in her lifetime.

"The thing about infertility in particular is that it doesn't care if you're a Democrat or Republican," she says. "It does not discriminate. So, there are people clearly on both sides of the aisle, with one in six people impacted by infertility, that probably need to access IVF."

"I'm cautiously optimistic that we'll we'll get it done," she adds.

This story first appeared on TODAY.com. More from Today: