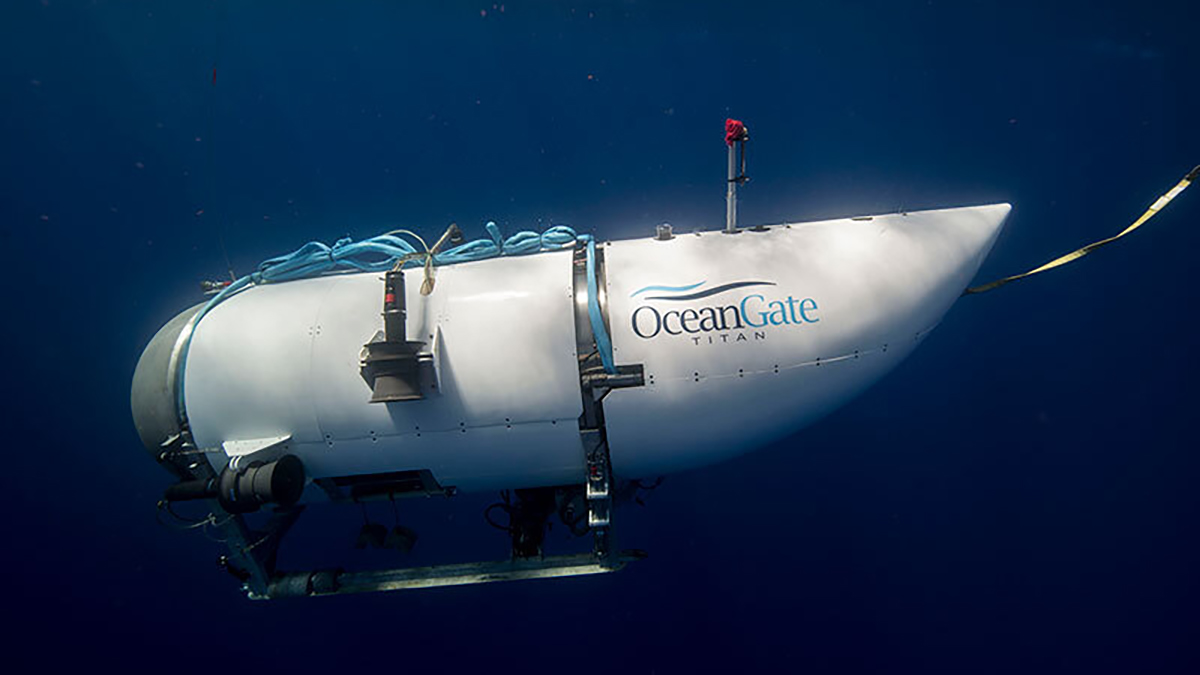

The implosion of OceanGate's Titan submersible last week, which killed the five people on board, has put the safety of ocean exploration in the spotlight — as did another Northern Atlantic underwater tragedy 60 years ago.

In April 1963, the U.S. Navy nuclear submarine USS Thresher imploded off the coast of Cape Cod, killing its 129 crewmembers and marking the deadliest submarine accident in U.S. history.

The USS Thresher was commissioned at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, during the Cold War, designed to cruise the ocean deeper than all previous submarines.

"The USS Thresher was a new class of submarine for naval applications, and it represented, really, the best of what was available at the time, and in terms of both its depth capability, its speed, its ability to support various weapons systems," said Andy Bowen, principal engineer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox.> Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

April 10, 1963, the submarine was conducting deep dive tests 220 miles east of Cape Cod when it lost communication with its accompanying ship.

This prompted a search for the ship carrying 129 people.

Two days later, the secretary of the Navy issued an official declaration that the Thresher and all on board were lost.

"I have the unequivocal assurance of all those in a position to know, including the Chief of the Bureau of Ships, the Commander, Submarines Atlantic and the Search and Rescue Commander on the scene that, in waters of this depth, there is absolutely no possibility that there might be survivors," read the news release.

President John F. Kennedy sent letters to the families of crew members, writing in part, "The loss of THRESHER was a great shock to freedom-loving people around the world. The American people feel deeply this tragic loss."

The search for Thresher continued, led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and the Naval Research Laboratory. Eventually, the ship's debris was located about 8,400 feet below the surface on the sea floor.

"The best estimates now are some failure in the plumbing, braised fittings that allowed sea water to enter the submersible and that led to difficulties controlling the depth which ultimately meant the submarine exceeded its operational depth and, as with the Titan submersible, was sadly imploded," said Bowen.

"It's important to remember that the ocean or sea water is 700 times more dense than our atmosphere and that adds up to many, many millions of pounds trying to compress our vehicles into a smaller space," Bowen continued. "And as engineers, it's an important challenge, of course, for us to design systems that are capable of withstanding crushing pressures."

More on the Titan submersible

The incident led to the creation of the Submarine Safety Program, or SUBSAFE, in 1963, and a complete change in safety checks and regulations that last to this day.

SUBSAFE is the quality assurance program of the United States Navy designed to maintain the safety of its submarine fleet. Specifically, this provides maximum reasonable assurance that submarine hulls will stay watertight and that they can recover from unanticipated flooding.

"I think we have, as a consequence of the tragic loss of Thresher, much safer submarines," said Bowen. "There has been no loss of a U.S. SUBSAFE submarine since that time."

He said the loss of the USS Thresher also motivated the development of tools such as the Alvin Human-Operated Vehicle, commissioned in 1964 as one of the world's first deep-ocean submersibles.

"Previous to that time, it was very difficult, sort of, if you will, searching the ocean with a flashlight which doesn't really shine very far in deep ocean darkness," said Bowen. "[Thanks to] the evolution of tools, we're able to move freely on the seafloor and perform a valuable service in terms of understanding the deep ocean. Alvin has since become really an important tool for the scientific community. And it's really rewritten the textbooks all the way from things like plate tectonics, to biology."

Given the danger of the deep sea, Bowen says the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is working on the advancement of technologies such as the equivalent of drones, the tethered vehicles that are engaged in the Titan recovery presently, or completely autonomous systems.

"We're working hard to sort of expand that human footprint notion to the application of some of these technologies," he said. "And I think it's fair to say that that's a really important part where some innovation is occurring. And it's, it's rapidly transforming our ability to understand the ocean, not a moment too soon."

As with the USS Thresher, he says lessons learned from the recent loss of the Titan submersible could help spur further improvements.

"I think one of the legacies of when a tragedy such as this occurs, is that we learn and take maximum advantage of what is an incredibly unfortunate and sad event, but can in turn, make what we do better," said Bowen. "And I think, in some ways, not that there's anything that changes the tragic loss of life, but in doing so, we actually maybe bring a little bit of purpose to what is a very sad event."

Each year, the 129 lives lost on the USS Thresher are commemorated in a memorial ceremony in Kittery, Maine, often including the surviving family members of the crew. This year marked the 60th anniversary.