In the age of streaming, easy and continuous access to music is just a click away. Gone are the days of perusing through plastic CD cases and going to the store to pick out the latest LP releases, but at least one place in New York City is keeping that history alive.

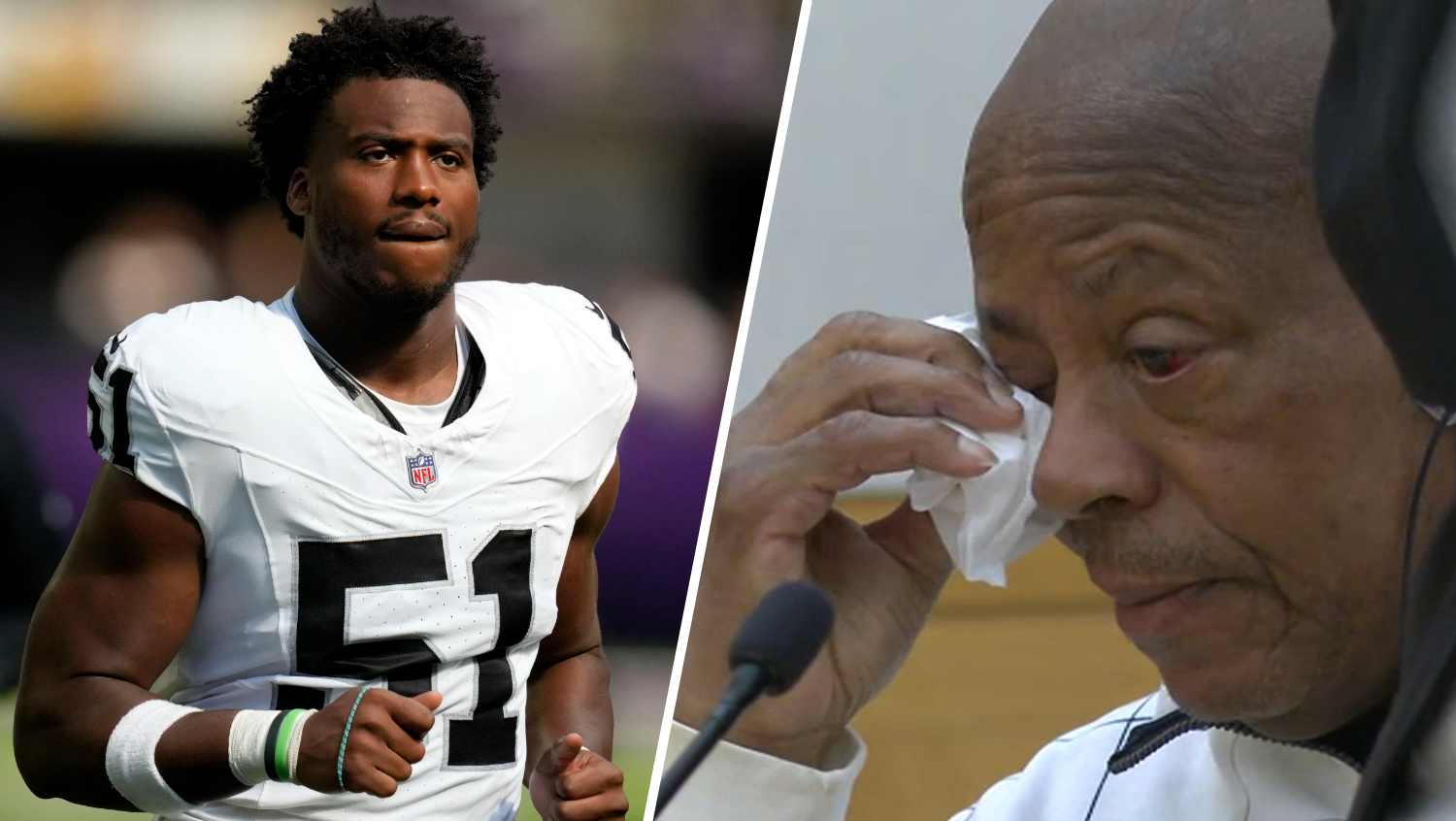

At Casa Amadeo, the city’s longest-running Latin music store located in the South Bronx, 90-year-old Miguel Angel Amadeo keeps the small shop running by himself. The Puerto Rican composer is a beloved figure in the community and the Latin music world. He has written and recorded hundreds of songs for some of the biggest stars like Celia Cruz, the queen of Salsa, and El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico.

"It's easier for me to tell you who didn't sing my song," Miguel joked. "If I start naming people, I'm going to have to name about at least a hundred, and if I didn't, they're going to hear about it and jump on me."

Miguel knows he's a pretty big deal. The street where his store is located, at the corner of Longwood and Prospect Avenue, was even named after him a decade ago. The store is also an official cultural landmark.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox.> Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

What made Casa Amadeo a musical institution is Miguel's decades of dedication to his business, which he bought from Victoria Hernandez in 1969.

Victoria opened the initial store "Casa Hernandez," which was a mixture of a music store and a variety shop, in East Harlem back in 1941 --- making it the longest operation Latin music store in the city. Miguel says that the sister of famous composer Rafael Hernandez was the only woman he recalled running a business like that at the time.

Local

The store first located in East Harlem, now known as Spanish Harlem. It was where many Puerto Ricans who moved to the U.S. mainland call their new home.

Miguel's father, Titi Amadeo, was among those who moved there in the 1930s in search of better economic opportunities following the Spanish-American War and World War II. Titi was a musician and composer too, but Miguel was just months old when he left.

"My father was a great composer," Miguel said, showing a CD where his dad was credited for one of the tracks.

Eventually, Miguel would follow in his footsteps. He and his mother moved to New York City in 1947, and as a Christmas gift for his first holiday in the city, Miguel said his cousin gave him a guitar. He taught himself how to play and he hasn't stopped since.

Inside his tiny music store, Miguel keeps immaculate records of all the compositions and lyrics he has written over the decades. He showed NBC New York how he wrote down the exact time and place that each pieces were conceived. Along side written records are photo albums filled with images of loved ones. One of those photos was a 1957 photo of Miguel in Germany where he served in the military.

"Gordo," he pointed at the photo and laughed.

When Miguel returned to Manhattan, East Harlem was increasingly becoming unaffordable as migrants competed for housing and jobs amid widespread segregation and discrimination. Back then, the majority of New York City's population were white Europeans and the fight for civil rights was at its peak.

Miguel's family then resettled in the Bronx. He got married and started working in the record department at ABC-Paramount, not far from where his store is now located, but he still wanted to record his own music.

Latin music, particularly Salsa, began gaining popularity in the 60s and Alegre Records was one of the major labels at the time. It was where legends like Johnny Pacheco, Tito Puente and Willie Colón were recording their music --- and Miguel and his band did as well.

“When we finished recording? They tell me why don’t you come and work for me," Miguel recalled. In addition to working in the record department, he was playing in nightclubs three times a week. Miguel said Alegre offered him the combined salary of his two jobs to work five days a week. With children on the way, the deal was too good not to take.

“I worked ten years with them. When I saw that they were going down, I decided to borrow some money and I saw that Rafael Hernandez’s sister was selling the store. She liked me a lot. She was sweet on me," Miguel said.

After buying the store from Victoria for just $5,000, Miguel began fixing it up and Victoria didn't have a problem with any of it. But when Miguel decided to change the name to Casa Amadeo, he said Victoria never stepped foot in the store again. Still, Rafael's memory is kept alive with his portrait in the middle of the store and the family name is still under the store's full name: Casa Amadeo, Antigua Casa Hernandez.

Running the store in the decades to come wasn’t always easy.

In the 1970s, the Bronx suffered the consequences of public policy that neglected marginalized communities. Issues of gentrification, redlining and housing discrimination all contributed to challenges faced by residents. One of the biggest threat to their livelihood at the time was rampant fires that were destroying neighborhoods.

"It was kind of rough," Miguel recalled. He pointed to a poster at the back of the store. It's from the PBS documentary "Decade of Fire," which chronicled upwards of 40 burnings a day and how it impacted the Bronx-native filmmakers.

“Everywhere you went. Everybody was burning their houses. So what they used to do is they burn the house to get the insurance. All the places was torn down," Miguel added. He said he used to have somebody watching the store for him when he wasn't around. It also helped that one of his sons was a police officer at the time.

"They don’t bother with me," he said.

For years, Casa Amadeo thrived, bringing in thousands of dollars in record sales weekly. Today, however, despite Latin music’s worldwide popularity, Miguel says he's losing money.

Streaming has drastically changed everyone consume music, and stores like his have become rare. According to the Recording Industry Association of America, Latin music streaming revenue grew by 17% in 2023, reaching $1.3 billion. CD sales, however, dropped by nearly half from 2022.

Despite the decline in physical music sales, Casa Amadeo remains a place of nostalgia, culture, and history. It’s not just a store; it’s a living archive. Friends drop by to reminisce and share stories, and music lovers from all over the world come to pay homage to this Bronx landmark.

Casa Amadeo has no website, no social media presence, and only accepts cash. Miguel wants it to remain that way.

"This is my life," he said. His beloved wife has passed away but she's buried nearby, and there's nothing else he'd rather do. When asked what would happen when he's gone, Miguel said his sons are not likely to take over the store.

"The only thing they could do is sell it to another store owner," Miguel said.

Whether people continue to buy CDs and records, Casa Amadeo is already more than a music store. It's part of New York City’s rich Latin music heritage and people come from all over the world to engage with its history.