What to Know

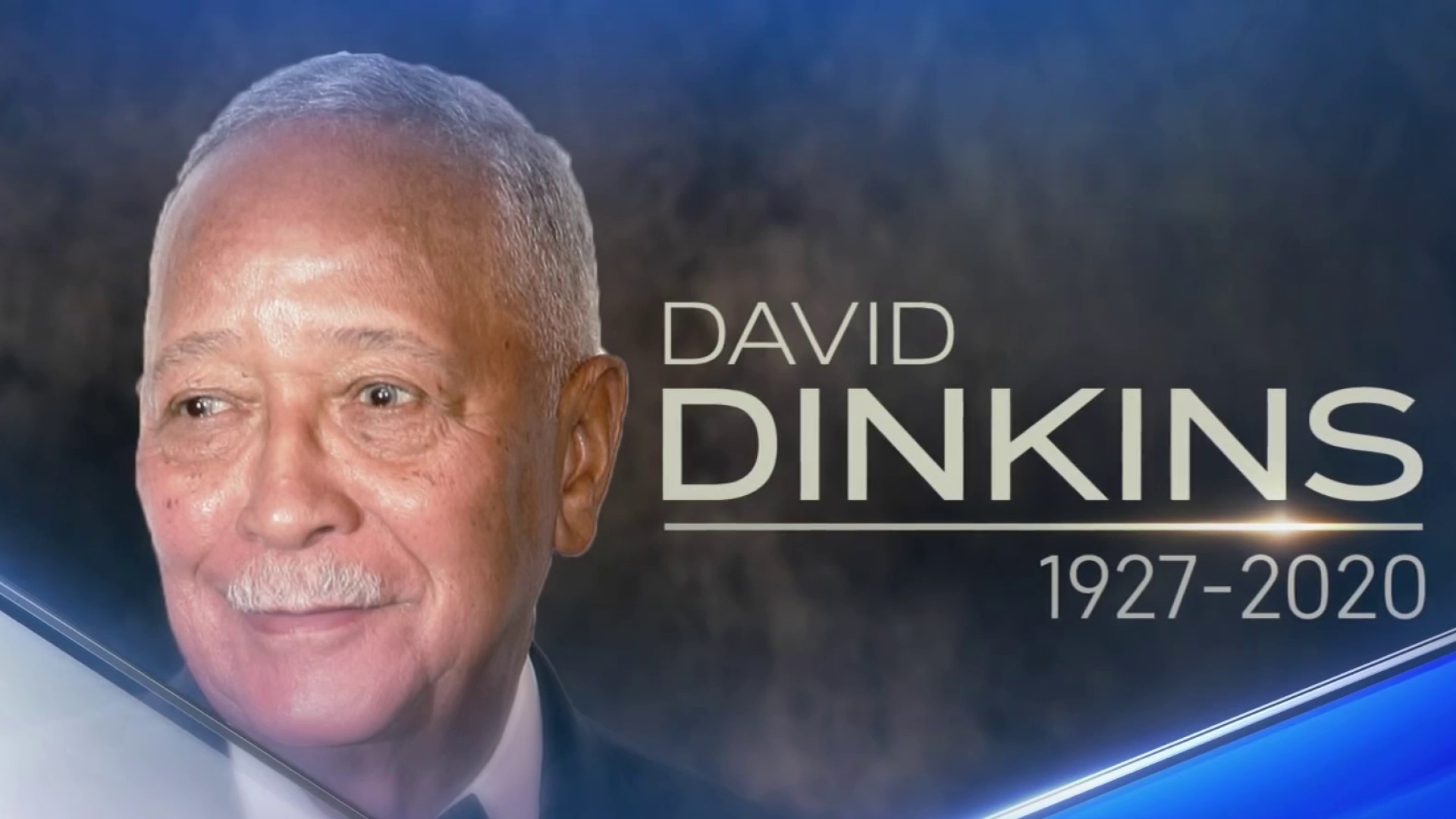

- David Dinkins, New York City’s first and only Black mayor, has died at 93.

- Two senior NYPD officials confirmed to NBC New York that Dinkins' health aide found him unresponsive in his Lenox Hill apartment Monday night, having apparently died of natural causes. The former mayor died a little more than a month after his wife, Joyce Dinkins, passed away.

- Dinkins briefly practiced law in New York City before he began his career in politics as a district leader and was elected a Harlem state Assemblyman in 1966. He went on to serve as President of the Board of Elections and City Clerk before winning election as Manhattan Borough President in 1985. He ran for mayor in 1989 and defeated Mayor Edward I. Koch and he went on to defeat Rudy Giuliani.

David Dinkins, New York City’s first and only Black mayor, has died at 93.

Two senior NYPD officials confirmed to NBC New York that Dinkins' health aide found him unresponsive in his Lenox Hill apartment Monday night, having apparently died of natural causes. The former mayor died a little more than a month after his wife, Joyce Dinkins, passed away.

"David N. Dinkins was a devoted family man whose love had no bounds. He extended his wealth of compassion to the citizens of New York City and beyond the five boroughs of its Gorgeous Mosaic," his family said in a statement. "As we mourn his passing, we cherish the legacy that he left behind. He showed us how to care for one another with dignity and grace. He fought for what he believed in and never compromised his principles ... He was a trailblazer who forged a path for others to follow. He will live on as today's and future leaders trace and advance from those footsteps."

Dinkins briefly practiced law in New York City before he began his career in politics as a district leader and was elected a Harlem state Assemblyman in 1966. He went on to serve as President of the Board of Elections and City Clerk before winning election as Manhattan Borough President in 1985.

Dinkins, who also served in the Marines in Korea, ran for mayor in 1989 and defeated Mayor Edward I. Koch and he went on to defeat Rudy Giuliani by the narrowest electoral margin in New York City history: 47,000 votes.

During his term as mayor from 1990 to 1993, Dinkins vowed to be "mayor of all the people of New York," and declared: "We are all foot soldiers on the march to freedom."

As the first Black mayor of the city, Dinkins inspired others to get into politics just as his father-in-law Daniel Burrows, a businessman who became involved in Democratic politics and was among the first Black men to serve in the state Assembly, inspired him. Among them was New York Attorney General Letitia James.

"The example Mayor David Dinkins set for all of us shines brighter than the most powerful lighthouse imaginable. For decades, Mayor Dinkins lead with compassion and an unparalleled commitment to our communities. His deliberative and graceful demeanor belied his burning passion for challenging the inequalities that plague our society," James wrote in a statement.

“Personally, Mayor Dinkins' example was an inspiration to me from my first run for city council to my campaigns for public advocate and attorney general. I was honored to have him hold the bible at my inaugurations because I, and others, stand on his shoulders."

Gov. Andrew Cuomo called Dinkins "a remarkable civic leader" who served the city "with the hope of unity and a deep kindness."

In his own inaugural address, Dinkins spoke lovingly of New York as a “gorgeous mosaic of race and religious faith, of national origin and sexual orientation, of individuals whose families arrived yesterday and generations ago, coming through Ellis Island or Kennedy Airport or on buses bound for the Port Authority.”

But the city he inherited had an ugly side, too.

AIDS, guns and crack cocaine killed thousands of people each year. Unemployment soared. Homelessness was rampant. The city faced a $1.5 billion budget deficit.

Dinkins’ low-key, considered approach quickly came to be perceived as a flaw. Critics said he was too soft and too slow.

“Dave, Do Something!” screamed one New York Post headline in 1990, Dinkins’ first year in office.

Dinkins did a lot at City Hall. He raised taxes to hire thousands of police officers. He spent billions of dollars revitalizing neglected housing. His administration got the Walt Disney Corp. to invest in the cleanup of then-seedy Times Square.

In recent years, he’s gotten more credit for those accomplishments, credit that Mayor Bill de Blasio said he should have always had. De Blasio, who worked in Dinkins’ administration, named Manhattan’s Municipal Building after the former mayor in October 2015. (De Blasio ordered city flags to fly at half-staff in Dinkins' honor Tuesday.)

"He was a guiding hand in our lives in so many ways," Mayor Bill de Blasio said of Dinkins during his daily coronavirus briefing Tuesday. "What he did for the city, he simply put us on a better path...He showed us what it was like to be a gentleman, to be a kind person, no matter what was thrown at him -- and a lot was thrown at him."

The current mayor went on to say that the greatest lesson he learned from Dinkins was "the power of love."

De Blasio said it was a "remarkable" experience to work alongside Dinkins, pointing out that Dinkins "never really got the credit he deserved," including for putting the city on the path to becoming safer.

Results from his accomplishments, however, didn’t come fast enough to earn Dinkins a second term.

After beating Giuliani, Dinkins lost a rematch by roughly the same small margin in 1993. Political historians often trace the defeat to Dinkins’ handling of the Crown Heights riot in Brooklyn in 1991.

The violence began after a black 7-year-old boy was accidentally killed by a car in the motorcade of an Orthodox Jewish religious leader. During the three days of anti-Jewish rioting by young black men that followed, a rabbinical student was fatally stabbed. Nearly 190 people were hurt.

A state report issued in 1993, an election year, cleared Dinkins of the persistently repeated charge that he intentionally held back police in the first days of the violence, but criticized him for not stepping up as a leader.

In a 2013 memoir, Dinkins accused the police department of letting the disturbance get out of hand, and also took a share of the blame, on the grounds that “the buck stopped with me.” But he bitterly blamed his election defeat on prejudice: “I think it was just racism, pure and simple.”

After news of Dinkins passing broke, Guiliani tweeted that Dinkins "gave a great deal of his life in service to our great City. That service is respected and honored by all."

Born in Trenton, New Jersey, on July 10, 1927, Dinkins moved with his mother to Harlem when his parents divorced, but returned to his hometown to attend high school. There, he learned an early lesson in discrimination: Blacks were not allowed to use the school swimming pool.

During a hitch in the Marine Corps as a young man, a Southern bus driver barred him from boarding a segregated bus because the section for blacks was filled.

“And I was in my country’s uniform!” Dinkins recounted years later.

While attending Howard University, the historically black university in Washington, D.C., Dinkins said he gained admission to segregated movie theaters by wearing a turban and faking a foreign accent.

Dinkins’ election as mayor in 1989 came after two racially charged cases that took place under Koch: the rape of a white jogger in Central Park and the bias murder of a black teenager in Bensonhurst.

Dinkins defeated Koch, 50 percent to 42 percent, in the Democratic primary. But in a city where party registration was 5-to-1 Democratic, Dinkins barely scraped by the Republican Giuliani in the general election, capturing only 30 percent of the white vote.

His administration had one early high note: Newly freed Nelson Mandela made New York City his first stop in the U.S. in 1990. Dinkins had been a longtime, outspoken critic of apartheid in South Africa.

In that same year, though, Dinkins was criticized for his handling of a black-led boycott of Korean-operated grocery stores in Brooklyn. Critics contended Dinkins waited too long to intervene. He ultimately ended up crossing the boycott line to shop at the stores — but only after Koch did.

During Dinkins’ tenure, the city’s finances were in rough shape because of a recession that cost New York 357,000 private-sector jobs in his first three years in office.

Meanwhile, the city’s murder toll soared to an all-time high, with a record 2,245 homicides during his first year as mayor. There were 8,340 New Yorkers killed during the Dinkins administration — the bloodiest four-year stretch since the New York Police Department began keeping statistics in 1963.

In the last years of his administration, record-high homicides began a decline that continued for decades. In the first year of the Giuliani administration, murders fell from 1,946 to 1,561.

One of Dinkins’ last acts in 1993 was to sign an agreement with the United States Tennis Association that gave the organization a 99-year lease on city land in Queens in return for building a tennis complex. That deal guaranteed that the U.S. Open would remain in New York City for decades.

After leaving office, Dinkins was a professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

He had a pacemaker inserted in August 2008, and underwent an emergency appendectomy in October 2007. He also was hospitalized in March 1992 for a bacterial infection that stemmed from an abscess on the wall of his large intestine. He was treated with antibiotics and recovered in a week.

Dinkins is survived by his son, David Jr., daughter, Donna and two grandchildren.