What to Know

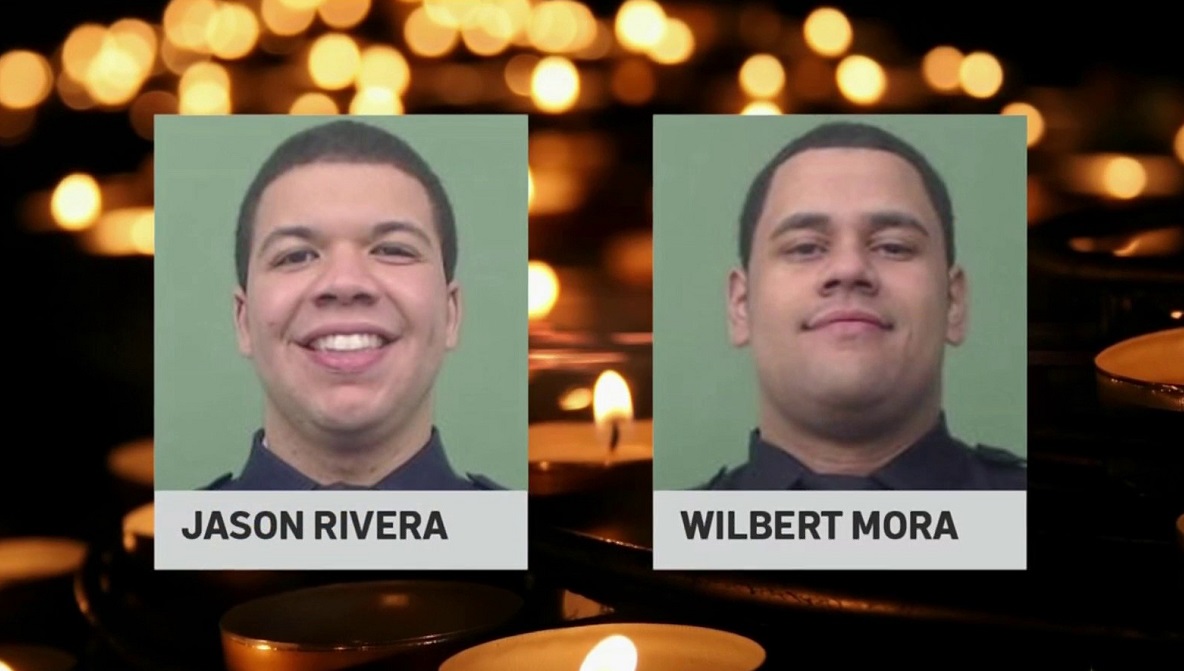

- Jason Rivera was no stranger to tensions between New York City cops and some of the communities they police. Growing up in a Dominican neighborhood in Manhattan, he’d seen it up close, like when his brother got pulled from a taxi and frisked for what felt like no reason.

- Wilbert Mora, too, knew it from his youth in East Harlem, and spent his college years thinking about ways to bridge the divide.

- Both sought to be catalysts of change when they became police officers, but were fatally wounded last Friday by a gunman who ambushed them while they responded to a call about a family dispute at a Harlem apartment.

NUEVA YORK -- Jason Rivera was no stranger to tensions between New York City cops and some of the communities they police. Growing up in a Dominican neighborhood in Manhattan, he’d seen it up close, like when his brother got pulled from a taxi and frisked for what felt like no reason.

Wilbert Mora, too, knew it from his youth in East Harlem, and spent his college years thinking about ways to bridge the divide.

Both sought to be catalysts of change when they became police officers, but neither got the chance they deserved. Both were fatally wounded last Friday by a gunman who ambushed them while they responded to a call about a family dispute at a Harlem apartment.

Rivera’s casket, draped in a green, white and blue NYPD flag, was carried into St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Thursday for his wake. Cardinal Timothy Dolan will preside over his funeral Mass there on Friday.

Get Tri-state area news delivered to your inbox.> Sign up for NBC New York's News Headlines newsletter.

A line of hundreds of mourners, many wearing uniforms and badges, wound through rows of barricades outside, waited in sub-freezing temperatures to pay their respects. Two officials from the Dominican consulate unfurled their country’s flag, in homage to the officers’ heritage.

JoAnn Pappert traveled an hour from Queens. Though she never met Rivera, she said she was compelled to be there by what she’d heard about his approach to policing.

“What he had in mind was something that was beautiful. It was something peaceful. He wanted to unite the community with the police department that, you know, has been struggling,” Pappert said. “I was really deeply touched by his vision.”

Rivera, 22, had been a police officer for barely a year. Mora, 27, was in his fourth year on the job. His wake and funeral Mass were planned for next week, also at the Roman Catholic cathedral.

Friends have been remembering the officers as caring and dedicated. Mora, a gentle giant with a strong physique and a warm heart and Rivera was a doting newlywed who’d FaceTime his wife from his locker.

Marisa Caraballo, a former neighbor of the Rivera family in Manhattan’s heavily Dominican Inwood neighborhood, said his mother objected when he told her he wanted to become a police officer. She said it was dangerous, but Rivera insisted and his mom relented.

“She said, ‘OK. I support you,’” Caraballo said.

Stephanie McGraw, founder of anti-domestic violence group We All Really Matter, said she got to know Mora during frequent visits to the police station where he worked.

“He was from from the hood,” McGraw said. “He understood the importance of getting into this very crucial and important role as a police officer — to not only make a difference but to bring some more men and women of color into the NYPD.”

Hundreds of officers and scores of residents attended a vigil for the slain officers Wednesday night.

“Officer Rivera and Officer Mora made a decision that they wanted to be part of the solution,” the Rev. Ronald Sullivan said. “We’re not believing the narrative that the community and the police are on different teams.”

In an essay describing why he became a police officer, Rivera recalled the injustice of being pulled over in a taxi and seeing officers frisk his brother.

“My perspective on police and the way they police really bothered me,” Rivera wrote. But he said he got interested in becoming a cop himself because he saw the department “pushing hard” to improve community relations.

Rivera and Mora were part of the newest generation of NYPD officers, one increasingly reflective of the city’s diversity.

As youths, they saw the end of “broken windows” policing that treated low-level offenses as a gateway to bigger crimes. They saw the court-ordered reduction in officers’ use of a tactic of routinely stopping young men and searching them for weapons.

Today’s NYPD is 45% white, 30% Hispanic and nearly 10% Asian. Black New Yorkers, who account for nearly a quarter of the city’s population, make up just 15% of its police force. The city’s newly appointed police commissioner, Keechant Sewell, is the first woman and third Black person to lead the department.

Before joining the department, Mora studied at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, where he impressed professor Irina Zakirova with sharp questions and a keen interest in striving for ways to build bridges between police and the neighborhoods they serve.

“He was so certain about becoming a police officer — a good police officer,” Zakirova said.

After it became clear that Mora wouldn’t survive the shooting, his family had his organs donated — in accordance with his wishes. Mora helped save five people with his heart, liver, kidneys and pancreas.

Rivera’s wife, Dominique Rivera, posted on Instagram that she and her husband were friends since childhood. She shared a message he wrote her in their school days saying he loved her and wanted to marry her.

After their wedding last October, Dominique wrote that Rivera was her “soulmate, best friend and lover from now until the end of time.”

“But now your soul will spend the rest of my days with me, through me, right beside me,” Dominique wrote over a picture of her husband’s police locker. “I love you till the end of time.”