The action in the Roundabout’s lavishly produced, but frustrating revival of Sophie Treadwell’s “Machinal” takes place in a rectangular room with thick, ash-hued walls. The room sits atop a turntable, and the set rotates — or lurches — 90 degrees with each scene change.

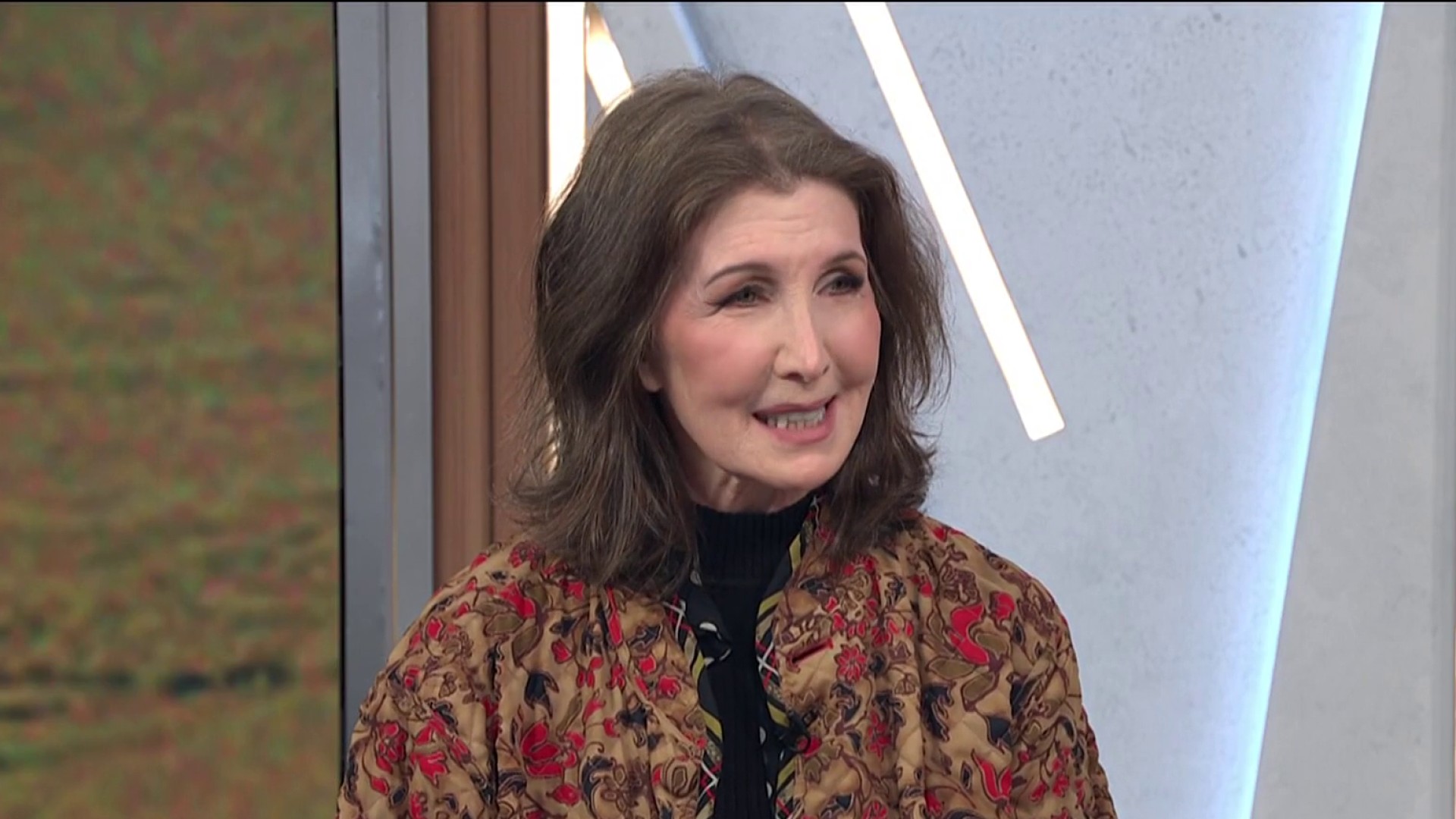

Both the shape and prison-like feel of the environment seem apt, since the protagonist of the 1928 Expressionist drama is a woman boxed in and suffocated by the people in her orbit. Guided by British director Lyndsey Turner and starring Rebecca Hall (a Golden Globe nominee for “Vicky Cristina Barcelona”), “Machinal” has just opened at the American Airlines Theatre. It’s the play’s first Broadway revival in 86 years.

Journalist and sometime-actress Treadwell’s narrative was inspired by the real case of a Queens housewife executed after helping her lover slay her husband. Ruth Snyder’s story became the basis for the film “Double Indemnity,” and Snyder’s electrocution at Sing Sing was captured in a famous New York Daily News photograph — that image has lingered so long in our collective consciousness that it made it into the album artwork for the 1991 Guns N’ Roses album “Use Your Illusion.”

As the 100-minute, nine “episode” “Machinal” unfolds Helen (Hall), a stenographer, is considering marriage to her doltish boss (Roundabout mainstay Michael Cumpsty, seen recently in “The Winslow Boy”), not for affection, but security. Helen’s mother (Suzanne Bertish, a Tony nominee for “The Moliere Comedies”) pushes the young career girl beyond hesitation one night, reminding her how foolish notions are of true love: “Love! … Will it clothe you? Will it feed you?”

In what reviewer Brooks Atkinson famously called “a tragedy of submission,” Helen’s life unfolds miserably in the pre-Great Depression era of money, men and machines — the play’s title, in French, translates to “mechanical,” and “Machinal” is at its core an account of the impact of industrialization on American society.

Fulfilling the expectations of those around her, Helen goes on a trip with her husband after their marriage, but she's repulsed by his touch. She bears him a child, but finds that she feels too detached from the baby to hold her. Then, on a visit to a speakeasy, Helen meets a man (Morgan Spector, “Harvey”) who offers her the emotional connection she so desperately craves. Their liaison sets in motion a chain of events leading to Helen’s condemnation.

The question posed by Treadwell is whether Helen is a victim of mores, or a narcissistic criminal, and the answer, at least in this production, seems to be both. Hall, a fine actress, plays Helen both as a woman ahead of her time and out of place in society — think Lena Dunham, in HBO’s “Girls” — and a naive fool, too-often concerned with the wrong thing at the wrong time. There’s a nifty, telling moment when Helen adjusts her hair in the seconds before her electrocution.

Broadway

Ultimately, though, Hall’s Helen doesn’t earn our affection, so her inevitable death never feels like the injustice we wish it did. The other difficulty with “Machinal” is the dialogue, delivered in the Expressionist style of the time as prescribed in Treadwell’s notes. What we get is rapid-fire staccato that makes every line sound like it’s Morse code: “I do – to love honor and to love – kisses – no – I can’t.” It’s grating, and not at all natural, though we are hearing it as the playwright intended.

Cumpsty is excellent as the naive patriarchal stereotype done in by his wife. A rough-and-tumble Spector is equally on point as the illicit lover who fulfills Helen’s image of what a man should be. His scene in a shared bedroom with Hall — she departs with a possession as a memory of their affair, a potted lily that proves pivotal to her conviction — is the play’s high point. (Of note: A young Clark Gable played the lover in the first Broadway production.)

That ominous set is by Olivier Award-winner Es Devlin, who also worked on the closing ceremony of the 2012 Olympic games.

In “Machinal,” the defining moment for Helen comes during her trial. The judge wonders aloud what those of us privileged to live in more sophisticated times have been thinking from early on: “If you just wanted to be free, why didn’t you divorce him?” Comes Helen’s reply to the jurist: “Oh, I couldn’t do that!! I couldn’t hurt him like that!”

“Machinal” is a tough piece of theater. Society drove Ruth — and so, for our purposes, Helen — to kill her husband. To actually be free, Helen has to die. How you ultimately view “Machinal” depends enormously on your sympathy for Helen and your ability to empathize with her actions. I just didn’t like Helen very much, so her death never felt like a terrible loss.

“Machinal,” through March 2 at the American Airlines Theatre, 227 W. 42nd St. Tickets: $52-$127. Call 212-719-1300 or visit roundabouttheatre.org.

Follow Robert Kahn on Twitter@RobertKahn